The world’s protected areas are largely a jumble of disjointed refuges, separated from each other by the encroachment of human impacts, a recent study has found.

Fewer than 10% of these parks and preserves are connected by intact habitat, the research, published Sept. 11 in the journal Nature Communications, found, even as opportunities for connections exist: More than 40% of the Earth’s surface remains intact.

“I was extremely alarmed by the findings,” Michelle Ward, the study’s lead author and a doctoral candidate at Australia’s University of Queensland, said in an email. “These results [mean] that more than 90% of protected areas are isolated in a sea of human activities. This should serve as a wake-up call to many countries.”

Some countries have been upping the proportion of their land that’s protected. When that land is intact, that’s a good thing for the species that call it home, Ward said, as it serves as a sanctuary from the wave of land uses like agriculture that can wipe out critical habitat and functioning ecosystems. Many governments have used the goal of setting aside 17% of their land and 10% of their coasts and the parts of the ocean under their control by 2020 as laid out in the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity’s Aichi targets to rally such efforts.

But not all protected areas are created equal. Ecologists worry that if they’re not linked to other intact areas, they might be little more than a statistic that doesn’t accomplish the goal of helping plants and animals weather the challenges they face on a changing planet.

“Connected landscapes ensure species can move through a landscape,” Ward told Mongabay. “Species travel for many reasons including seasonal migrations, finding a mate, moving away from close relatives to ensure genetic diversity, escaping natural disasters such as fires, or tracking their preferred climates (especially under rapid human-induced climate change).”

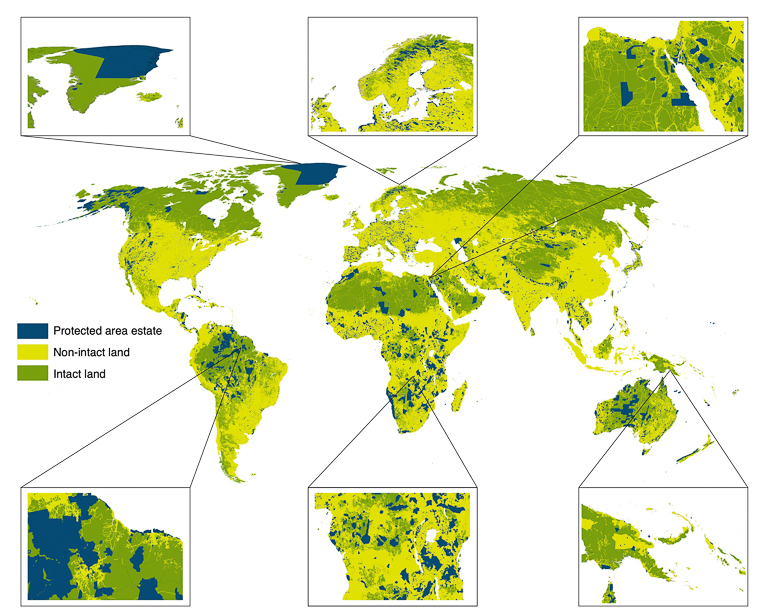

She and her colleagues looked for linkages between protected areas where humans have had minimal impact on the landscape using the human footprint data set. The human footprint map pulls in data on the myriad ways we humans affect natural habitats, from roads and railways to cities and farmland. The team’s analysis revealed that 41.6% of the world’s surface is intact. But the team also discovered that only 9.7% of the world’s protected areas are joined by stretches that are relatively free of human impacts and thus qualify as intact.

That doesn’t mean that connectivity is a panacea for all species, Ward said.

“Connectivity is difficult to measure because species use the landscape [in] different ways,” Ward said. “Some species, such as lions in Africa, use roads to traverse into neighbouring habitats, [and] other species require areas far from human modifications to be able to move through the landscape.”

Still, the global measure of the quality of landscapes is something that hasn’t been possible until now, she added, “in the age of big data.”

The research identified several countries, including Brazil and Peru, as well as Greenland, a self-governing territory of Denmark, that had reached the Aichi target of more than 17% of land area protected and had greater than 50% connectivity.

But other spots like Vietnam and Madagascar — both bastions of unique species and high levels of biodiversity — are lagging, Ward said. The analysis showed that only about 8% of Vietnam’s land area is protected, and none of the reserves is connected to any others.

Madagascar’s figures are even lower, with 4.2% of its land mass under some form of protection will no “fully connected” protected areas, Ward said. She added that tree-dwelling animals like the more than 100 species of lemur living in the island nation are particularly sensitive to the loss of connected forests.

Ward said that the study could be a valuable tool for both scientists and governments in sorting out the remaining, irreplaceable areas of habitat as well as targets for protection and restoration between them.

“We desperately need to retain our last remaining intact and connected areas,” she added. “For these areas to be retained, they must be formally recognized (through protected area status or other effective area-based conservation measures), socially accepted, prioritized in spatial plans, economically viable, and then effectively managed, so they can be protected from human impacts.”

Leave a comment