Most people might not have heard of the Framingham Heart Study. But the massive public-health research effort, now in its 77th year of conducting in-depth analysis of more than 15,000 people, is the source of many insights we now have into healthier aging. It inspired the first checklist for assessing heart disease risk, and our current understanding of how to reduce cardiovascular disease can be traced directly to its findings.

While the Framingham Heart Study started off solely focused on heart health, following a large subset of the inhabitants of a former mill town on the outskirts of Boston throughout their lives, it is now providing information about the brain, liver, and many other organs.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

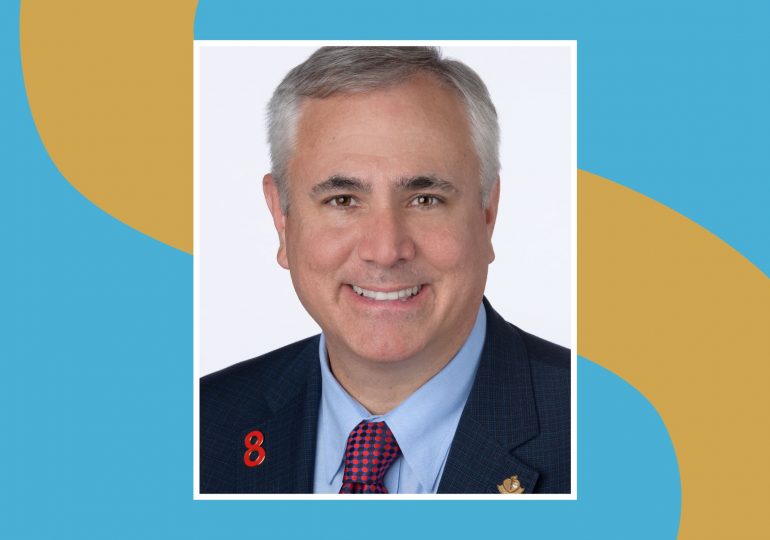

As part of TIME’s series interviewing leaders in the longevity field, we spoke to epidemiologist Dr. Donald Lloyd-Jones, the current head of the study and a professor at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, about the study and what it tells us about aging well.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What is the Framingham Heart Study?

It’s the longest-running community-based study in the world. Its origins lie in finding the root causes of cardiovascular diseases, especially heart attacks and strokes. In 1948, the people who designed the study enrolled about a third of the population of the town of Framingham, Massachusetts, which is about 20 miles west of Boston. They really wanted to understand what was causing the emerging epidemic of heart disease after World War II.

It was already the leading cause of death, but it was quite clear that it was on the rise, and it wasn’t well-understood why that was happening. There were some very good hypotheses implying that diet and cigarette smoking might be linked, but it had never really been shown systematically or consistently.

They started to understand that it would be valuable to have families involved in this study—that heart disease is not just a man’s disease, and that there might be some familial component. They hadn’t even discovered DNA yet. This is decades before thinking about genetics.

Read More: How Tracking Your Health Metrics Can Help You Live Longer

They saw all of the participants every two years and did a full physical examination, collected blood, measured height and weight, things like that. They asked, What were they doing? What were their health habits? Really deep data collection for what was available at the time.

By the early 1960s, they had a strong signal that, in fact, blood cholesterol levels were tightly linked to risk for cardiovascular disease. Blood pressure was especially tightly linked to risks for cardiovascular disease and smoking. Pretty quickly thereafter, they could see that body weight was related, that sedentary lifestyle was related, certain aspects of diet were related.

So Framingham is really the study that put what we now consider the traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease on the map.

What happened next?

They enrolled another 5,000-plus individuals who were the offspring of the original participants and the spouses of those offspring. So we’re starting to get the genetic linkages, but also the environmental linkages—the shared environment between spouses. It was decades before we understood these things were important, but there were inklings, and they were smart enough to listen to those signals. So the offspring cohorts get examined about every four years, in addition to the first cohort being examined still every two years. That goes on through the 1970s and 80s and 90s.

We start to understand more about not just total cholesterol, but the subcomponents of cholesterol. We start to understand more that it’s actually your systolic blood pressure that’s more dangerous for you than your diastolic blood pressure. Certain types of dietary factors, certain types of physical activity were better.

Fast forward another few decades: in 2002, Framingham enrolled the third generation of related individuals. Along the way, the town of Framingham was actually changing pretty dramatically. Originally, back in 1948, Framingham was a town largely made up of people from European ancestry. It was a mill town, so there was a broad stratification socioeconomically, but it was pretty homogeneous in terms of race and ethnicity—almost exclusively white. But by the 90s and 2000s, there were lots of people of Asian heritage; a lot of Brazilian people settled in Framingham, so it became a much more diverse community.

Read More: Unlocking the Secrets to Living to 100

In total, we’re following six different groups of people, all of whom are related to Framingham in some way. And now there’s the technology to fully sequence someone’s DNA, and understand modifications to that DNA, called epigenetics. We can collect data on what their cells are actually transcribing. We can collect data on proteomics, metabolomics, microbiomics, and there are new technologies to help us look inside the body non-invasively, so we can see disease developing in the cardiovascular system, in the brain and the kidneys.

There has been a huge explosion in the ways we can characterize people. And Framingham has really been a leader all along in understanding the process of aging in every organ system in the body. Yes, we are still the Framingham Heart Study, but we have just as much activity going on in brain health across the life course, and lots of activity looking at bone health, kidney health, lung health, liver health—you name it—because these people are so well studied across their entire life course.

What kinds of things can people do to reduce the risk of diseases of aging?

The American Heart Association has kind of a nice way to package this all together, called Life’s Essential Eight. It’s a platform in which people can measure their cardiovascular health status today. It’s also linked to really positive health outcomes over time, and it’s influenced by evidence from the Framingham Heart Study.

The eight components are not going to surprise you, but they’re all actionable. They’re all modifiable, and they’re all things that people can do today to improve their cardiovascular health, which has been shown to reduce their risk for Alzheimer’s disease, all forms of cardiovascular disease, even cancer, arthritis—all the things that we worry about as chronic diseases of aging. If you focus on your cardiovascular health, you’ll have benefits for all these things simultaneously.

Read More: Want to Live Longer? First Find Out How Old You Really Are

So what are the eight components? They are a healthy diet, participating in physical activity, avoiding all forms of nicotine exposure (combustible cigarettes, but also other forms of nicotine exposure, because they’re toxic, too), healthy sleep, healthy weight, healthy blood pressure, healthy blood sugar, and healthy blood lipids.

No surprises, but here is what this is about: How can we optimize your health today, so that we extend not only your lifespan, but your healthspan—meaning not just the years in your life, but the life in your years?

Can we make the date that you get sick much later—much closer to the time you’re going to die—so that you have more healthy years, not just more years, period?

We don’t seem to necessarily be doing what the science suggests, as a society. Why is that?

The truth is, although we’ve known that for 60 years, we’re still terrible at implementing it in public-health policies and in clinical practice. It’s a pretty simple message, but we don’t design our society, our environment, our neighborhoods, or our food supply to optimize those things.

It is possible to take this information and make a change. Great story: In the early 70s, Finland had the highest coronary heart disease death rates in the world, by a fair amount. They took information from Framingham and they said, You know what, let’s design a study where we take a county with particularly high coronary disease death rates and we just make some public-health changes. We’re going to implement smoking policy changes. We’re going to help people quit. We’re going to stop subsidizing meat, and we’re going to start subsidizing fruits and vegetables in our food supply.

Read More: Scientists Say These Daily Routines Can Slow Cognitive Decline

Immediately, the rates of coronary heart disease started to fall, and the strategies were soon applied across the country. By 30 years later, there was an 84% decline in coronary disease death rates, and suddenly Finland has the lowest coronary disease death rates in the world—so going from last to first.

In the U.S., we saw about a 70% decline in death rates from heart disease between 1968 and 2010, because we’ve gotten better clinically, and we’ve done some things with public health.

Unfortunately, I think while we were making really, really great progress, the obesity epidemic has started to really kick in on the burden of cardiovascular diseases. Because obesity will drive higher blood pressure, higher blood sugar, more adverse cholesterol levels—all sorts of things—that sort of becomes a perfect storm. Since 2011, we’ve now seen leveling off of those improvements in death rates and maybe even some reversal, which is unfortunate. We understand everything we need to know about preventing cardiovascular disease. As we actually implement that, we’ll expand healthy aging.

What does the future hold for the Framingham Heart Study?

Well, you may have heard that funding for science is a little difficult these days. But my hope would be that we would continue to represent the town of Framingham. I think there could be real value also for enrolling our fourth and our fifth generation.

The more we’ve studied the life course of all these chronic diseases, the more we’ve understood that every time we get a diagnosis, the horse is already partly out of the barn, if not all the way. So we need to get much, much earlier in the life course with prevention.

Read More: Your Brain Reveals a Lot About Your Age

I’ll leave you something hopeful. In another community-based study—a kind of descendant of the Framingham Heart Study—when they looked at how long people lived without cardiovascular disease, they found that lifestyle wins. Even people with high-risk genes, if they have a good lifestyle, they on average live 12 years longer than people with good genes but poor lifestyle habits. What’s more, they live 19 years longer on average without cardiovascular disease.

They not only extended their lifespan; they extended their healthspan substantially.

Genetics are not destiny. We can actually bend that curve, and people can do better if they can pursue these healthy lifestyle options. So much of this is actually in our control. But we need help: We need help from our food supply. We need help from good public-health policies so we are not exposed to indoor air that is contaminated by cigarette smoke. We need safe streets to go out and do physical activity. We need to actually be able to afford to buy fruits and vegetables.

A lot of this is policy that sets the stage. But there’s a lot in our control as well.

This article is part of TIME Longevity, an editorial platform dedicated to exploring how and why people are living longer and what this means for individuals, institutions, and the future of society. For other articles on this topic, click here.

Leave a comment