As winter ends, several viruses are still continuing to rise across the U.S., according to data from WastewaterSCAN, a network of wastewater surveillance sites. Norovirus, one type of influenza, and another respiratory virus are all increasing or have recently peaked in samples from the network’s 190 wastewater treatment facilities, which are located in 41 states.

“What we’re seeing right now for the major viruses we are monitoring is that there are similar patterns across the country,” says Marlene Wolfe, assistant professor of environmental health at Emory University and one of WastewaterSCAN’s program directors. “We’re not seeing widely divergent patterns geographically.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

When people are infected, they shed viruses in their excretions, and analyzing samples from wastewater treatment plants is an efficient way to get almost real-time information on what’s ailing people in a given community. This type of data is especially useful when people don’t get tested at hospitals or doctors’ offices—and therefore aren’t registered in official case counts.

In general, the samples are picking up fewer cases of COVID-19 and influenza A, the type of flu that tends to cause more serious disease. RSV rates have also been steadily declining. Those patterns are typical as winter comes to a close.

But these other viruses make it clear that sick season isn’t over yet.

Norovirus

The so-called “cruise ship virus” is very contagious and responsible for just over half of all food-borne illnesses in the U.S. each year. Cases generally build from November to April, and this year, infections have followed that rising trend, according to the WastewaterSCAN data. Last year, cases peaked earlier, at the end of February, says Wolfe, but infections only started inching down in the past few days. However, norovirus does not tend to strictly follow seasonal patterns, she says, because food-borne contaminations can occur at any time of the year.

Read More: Here’s the Best Way to Cure an Upset Stomach

The best way to avoid the diarrhea and vomiting that infections cause is to thoroughly clean high-traffic surfaces, such as kitchens and bathrooms, and for public facilities like day care centers and schools to follow those same practices. “I remind people to use bleach if they have a norovirus problem,” says Wolfe. “Hand sanitizer will not remove and inactivate this virus—it likes to stick around.”

Human metapneumovirus (HMPV)

HMPV was identified relatively recently, in 2001, although scientists believe it has been circulating for half a century. It belongs to the same family of viruses as RSV and affects similar populations—older people and younger children—by causing respiratory disease. Improved testing methods have helped health officials get a better sense of how prevalent infections are.

Many doctors and health centers don’t test for the virus, but wastewater sampling can easily detect it. Collection sites have picked up a sharp increase in the virus since late February, and levels have continued to rise, only recently starting their descent. Wolfe says that HMPV is a late bloomer, with infections picking up when flu and RSV drop, so it’s not unusual to see more cases in the late winter and early spring.

Read More: The New RSV Drug Keeps Babies Out of the Hospital

There is no specific antiviral treatment for the virus, but health experts say the usual habits of hand-washing, covering coughs and sneezes, and staying home if you have a fever or don’t feel well can help reduce the spread.

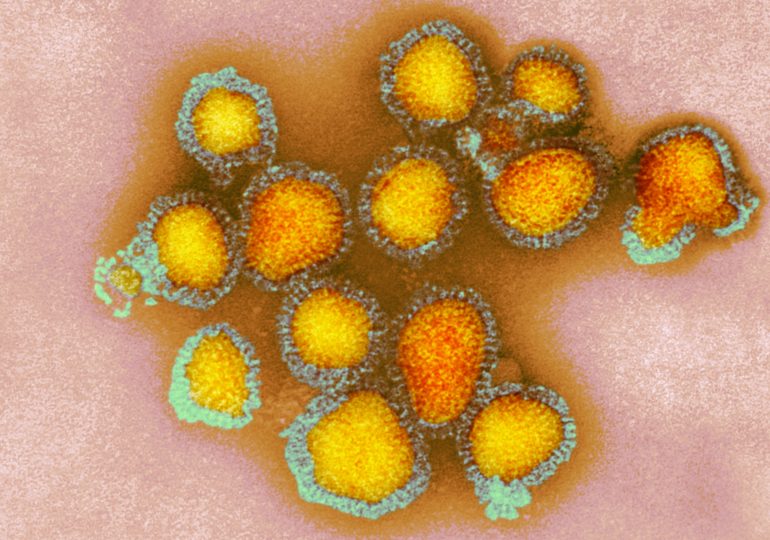

Influenza B

There are four types of influenza viruses—labelled A, B, C, and D—but the viruses that return every year and cause the most problems belong to the A and B groups. Influenza A viruses tend to cause more serious disease in people and are responsible for large outbreaks and pandemics such as H1N1 and H3N2, because of their ability to mutate and change their genes more quickly. Influenza B viruses are slower to mutate, but can still cause illness especially among vulnerable groups like older people and those with weakened immune systems.

While influenza A viruses are declining in nationwide samples, B viruses have continued to rise and have only very recently peaked, says Wolfe. That’s a different pattern from last year, when there was much less influenza B overall, and those viruses peaked earlier.

The good news is that the annual flu shot is designed to target both influenza A and B viruses, so most vaccinated people don’t need to take precautions beyond washing hands frequently and covering coughs and sneezes. Getting a flu shot at this point in the season won’t hurt, but it’s not likely to be as protective as immunizations earlier in the season, since cases—and therefore the risk of infection—will start to decline rapidly in the spring.

Read More: This Is the Best Time to Get a Flu Shot

Even though it’s late in virus season, for scientists and vaccine makers, the wastewater information is valuable; it gives them insights into which types of viruses to continue targeting in the shots, and how long any protection provided by the vaccines will need to last to reduce serious disease.

Wolfe is encouraged by the consistency and reliability of wastewater surveillance in tracking infectious diseases, and says more pathogens will likely be monitored in this way to help health officials better manage them. “This tool has matured since we started doing research on wastewater and COVID-19 in March 2020, and it’s really exciting and gratifying to see how useful it is for individual and public health responses for a much larger suite of viruses,” she says.

Leave a comment