As popular as the new group of weight-loss drugs like Wegovy and Zepbound are, not everyone responds to them in the same way.

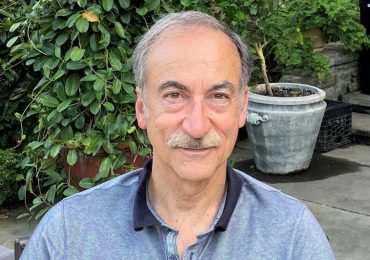

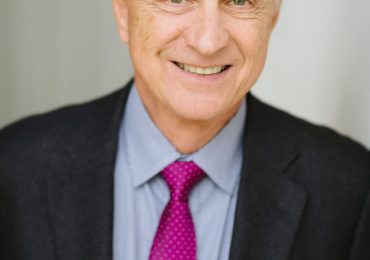

In a new presentation at the Digestive Disease Week conference in Washington, Mayo Clinic associate professor of medicine Dr. Andres Acosta reported that a genetic test he developed can identify which people are most likely to respond to semaglutide (Wegovy) and which are not.

The test, called MyPhenome, from a company Acosta co-founded called Phenomix, relies on a combination of genetic and other factors to categorize people into different types of weight gain. Acosta identified about two dozen genes linked to obesity, and more than 6,000 variants of these genes, to sort people who struggle with weight gain into four categories:

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Hungry Brain: People never feel full, despite how much they eat

Hungry Gut: People eat until they are full but then feel hungry again an hour or so later

Emotional Hungry: Those who eat to cope with emotional issues or to reward themselves, regardless of their physiological signals of hunger

Slow Burn: People who simply aren’t able to burn calories as quickly as they take them in.

In his latest presentation (the results of which have not yet been published in a journal), Acosta reports that the MyPhenome test for Hungry Gut predicts with 75% accuracy who will respond to semaglutide.

“That comes with huge implications—first for the patient, because there is no more trial and error, and second, as a physician, I want to know which of my patients will respond because I am asking them to spend $1,000 a month or pay a high copay if their insurance covers the drugs,” he says. Having a better idea of whether a person will respond to drugs like Wegovy could also relieve access issues by steering only the best candidates toward it. “This could change the way we manage obesity,” he says.

Read More: Is Ozempic the New Anti-Inflammatory Wonder Drug?

The study involved a small number of patients—84 people who were overweight or obese, only some of whom had diabetes—who provided a saliva sample for the MyPhenome test for genetic analysis and also answered a questionnaire about their eating habits. Each took semaglutide for a year, and most reached the maximum dose. Because the Hungry Gut profile involves appetite, and semaglutide works by suppressing the desire to eat, Acosta found that people who fit into this category were most likely to lose the most weight on semaglutide. In the study, 51 of the 84, or about 60%, were classified as Hungry Gut.

“Patients with Hungry Gut lost 19.5% of their body mass after a year, compared to 10% for those who were Hungry Gut negative,” says Acosta. “That’s almost double the amount of weight loss. For the first time, we can identify the best responders.”

Acosta and his team say larger studies replicating these initial findings need to be completed before the test can be used more widely. For now, doctors can order the MyPhenome test for patients from Phenomix’s website and use it as another piece of information to help them and their patients decide if the drug is a good fit.

“My dream is to treat chronic diseases like obesity in the same way we treat cancer—in a very precision-based manner,” says Acosta about the next steps for the test. It’s also possible that as more next-generation weight loss drugs are approved, pharmaceutical companies may simultaneously develop screening tests to identify people who are most likely to benefit from their drugs. Insurers may also start relying on such tests in making reimbursement decisions to ensure that patients are receiving the right treatments for them.

Acosta says the potential of the test isn’t limited to semaglutide. For some people, some of the older weight-loss medications may be just as effective, but until now, doctors relied on a trial and error method of prescribing them. With more precise ways to matching patients to the medications that work for them, all of the existing weight-loss drugs could be better optimized to the right patients.

Leave a comment