In our latest post, Claudio Açaí Bracho-Estévanez shares with us how intricate the relationship between producer and consumer is! Claudio explains the beauty behind their paper: ‘Plant traits determine seed retention times in frugivorous birds: Implications for long-distance seed dispersal‘, which explores how seed size also serves as an important factor for how long seeds can be retained and dispersed in frugivorous birds!

About the paper

Many plants rely on fruit-eating animals (frugivores) to disperse their seeds. Frugivores consume fruits and retain the seeds in their digestive tracts for a period called “retention time”. Hence, retention times are crucial in determining how far seeds can be dispersed and where they end up, which has important implications for plant populations and communities. Larger frugivores generally retain seeds longer than smaller frugivores, so it’s generally accepted that the body size of frugivores is positively related with retention times. However, little is known about whether plant-species traits affect seed retention times. If so, different plant species would differ in their dispersal potential, especially when dispersal requires long-distance directional movements such as those of migratory birds. We addressed these questions by conducting experiments with captive songbirds (passerines) that were fed with fleshy fruits to measure seed retention times. Additionally, we reviewed data from published studies on retention times to analyse a larger dataset with songbird and non-songbird species. We found that seed size negatively affected retention times and, interestingly, this effect is indirect, mediated by the type of seed ejection: larger seeds are regurgitated quickly, while smaller seeds are generally retained longer and defecated. Notably, seed size effects were comparable to that of frugivore body size in songbirds. While fatty pulps slightly increased retention times, this effect was very minor compared to seed size. Our findings suggest that plant species vary in their ability to be dispersed over long distances by frugivorous birds. Additionally, through our paper, we offer new methods for estimating seed retention times. This an greatly improve seed dispersal models, highlighting the strong link between seed size and retention times!

About the research

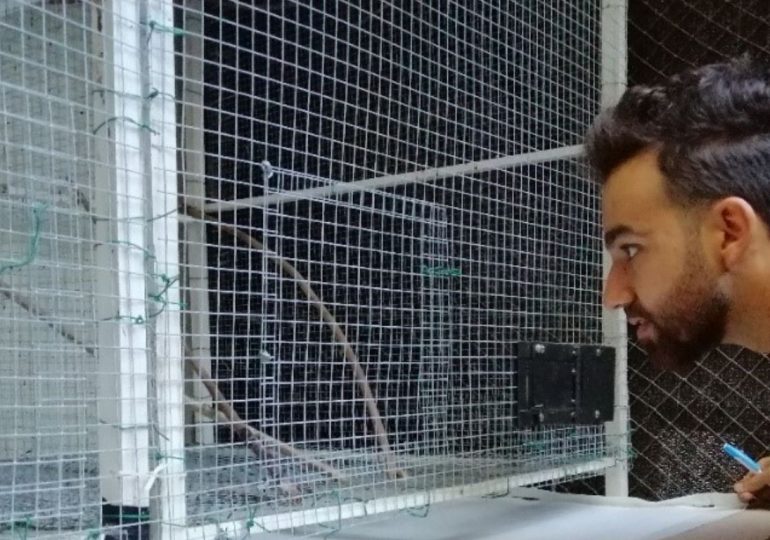

Our research findings represents a step forward in the field of frugivory and seed dispersal research. The experimental process was both challenging and fascinating. Our experiments consisted of recording seed retention times, that is, the time elapsed from seed ingestion to seed ejection. To do so we used video cameras to monitor captive birds feeding on fruits and ejecting their seeds placing a seed deposition tray under bird cages to visualize and retain ejected seeds. One of the most memorable aspects of this research was observing the birds’ behaviour day after day. Spending countless hours watching how birds consume fruits and eject seeds provides insights that extend well beyond what can be explained in a manuscript. The first days of training were perhaps the hardest, since we had to train birds to follow a precise feeding procedure with fruits available only during short time intervals. Thankfully, the expertise of the dedicated staff at the Zoobotánico Jerez was invaluable! A surprising finding was the “only-defecation” digestive processing of blackcaps, since the rest of bird species both regurgitated and defecated seeds. Contrary to our expectations, the type of ejection of seeds was not related to body size, yet it was critical in explaining variation on seed retention times. The next important task involves exploring how variation between plant species and their seed retention times in birds, impacts seed dispersal at long distances, which is critical for plant redistribution in the face of anthropogenic climate change.

About the author

I am a PhD student at the University of Cádiz. Similar to many ecologists, I was driven by a passion for nature that sparked my interest in ecological research. Growing up as a birder in the outskirts of Barcelona, I became fascinated by how diverse species interact with our environment and how human activities may disrupt these interactions. The proximity of natural areas was crucial, with long journeys exploring nearby wetlands and maquis shrublands. After earning my degree in environmental biology from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, I decided to specialize in ecology and geographic information systems. This journey brought me to PAISAJE lab (www.paisajelab.es) in the University of Cádiz, where I have been inspired by an amazing team devoted to the study of frugivory and seed dispersal. My advice to young students is to stay curious, constant, and passionate about your field of research, then good opportunities will come!

Like the post? Read the research here.

You can find out more about the work that the PAISAJE lab is doing here.

Leave a comment