When George Thurston leaves his cottage in the woods of Waccabuc, N.Y., to head for work, a pollution monitor clipped to his belt—called an AirBeam—shows pristine air quality. As he takes the train through the suburbs, the device’s digits rise, meaning more pollution. By the time he gets to his office in Manhattan, they’re even higher.

“It’s important to know your exposure profile to protect against everyday cumulative risk,” says Thurston, professor of medicine and population health at NYU’s School of Medicine.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

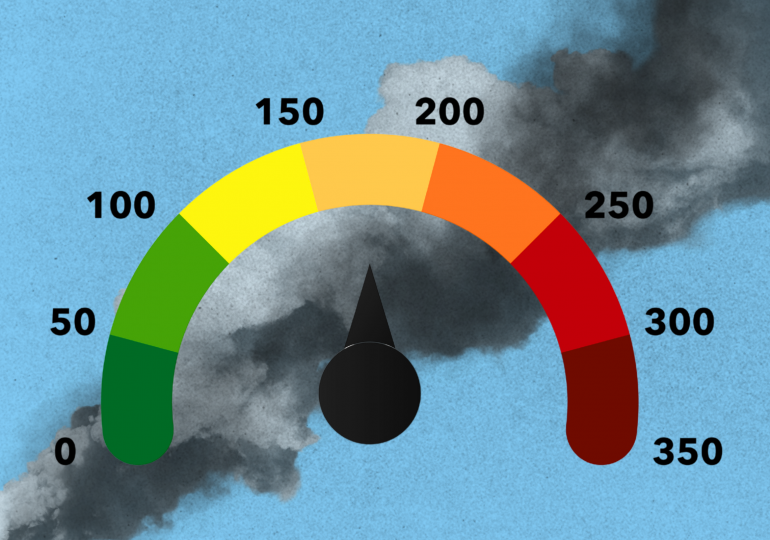

Compared to other toxins in the environment like plasticizers and pesticides, outdoor air pollution is the most harmful type based on current evidence causing millions of deaths per year. Using an air quality index (AQI) is one way to tell how polluted the air you’re breathing is. Many AQIs—from the readouts on Thurston’s gadget to ones based on gold-standard detection stations built by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency—have been developed to monitor pollution and inform you when being outside is safe.

But their assessments and forecasts often conflict. “The different data streams have their own biases and assumptions,” says Makoto Kelp, assistant professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Utah. “I don’t think they’re very well communicated to the public.”

With harmful particles in the air partly due to intensifying wildfires, here’s how to figure out your personal risk for outdoor air pollution to protect your health.

Why your air quality matters

Death certificates list causes like heart disease, stroke, and cancer, but these diseases have their own causes. They’re shaped by underlying forces, including air pollution in many cases.

Pollution isn’t just one thing; it’s a mix of toxins from vehicle emissions, coal-fueled power plants, and natural gas used to heat buildings. Such substances contain dangerous material called particulate matter 2.5. Much thinner than a strand of hair, PM2.5 can penetrate deep inside the body, where it drives many of pollution’s health impacts.

Read More: Weighted Vests Are the Latest Fitness Trend. Do They Work?

Take dementia. “Every reduction in pollution matters,” says Haneen Khreis, senior research associate at Cambridge University. Earlier this year, her team studied long-term exposure and found that, with every 10 micrograms of PM2.5 (per cubic meter of air) we’re exposed to, dementia risk increases by 17%. (For perspective, 10 micrograms of PM2.5 is the average roadside measure in central London.)

If you already have a chronic disease, “poor air quality may make it worse,” Khreis explains. According to Thurston’s research, the month after a Pittsburgh plant stopped emitting fossil fuels, emergency hospital visits for pediatric asthma dropped by 41%—and continued declining after that.

The trouble with tracking pollution

We can protect ourselves from pollution only if we know it’s there. AQIs focus on tracking and forecasting the most widespread pollutants: PM and ozone.

The EPA posts its AQI on AirNow. Other AQIs are provided by weather apps like AccuWeather and companies like PurpleAir that share readouts from their networks of privately owned sensors.

These AQI values frequently diverge because each organization compiles its own data before converting their findings (with the EPA’s formula) into a 0-500 risk score. There’s no consensus on which data to use partly because the science of monitoring and predicting air quality is so complex. “There’s more randomness and uncertainty, compared to weather forecasts,” Kelp says.

AQI forecasts are easily scuttled by the wind. Both its speed and direction can change on a dime. Pollution tends to travel with moving weather masses, says Jonathan Porter, chief meteorologist at AccuWeather, a company that tracks and forecasts weather including air pollution. If the wind shifts from polluted areas nearby, the unhealthy air could quickly blow into your area. Or your AQI could improve if the wind picks up in the lower atmosphere, suddenly dispersing stagnant, pollutant-filled air.

AQIs may also lag behind unforeseen temperature changes. Strong sunlight can worsen air quality by driving chemical reactions like ozone formation.

Another complication: it’s hard to calculate mixtures of pollutants in the air, so AQIs focus on whichever pollutant is currently highest—more of a sketch than a full portrait. Researchers have found that the EPA’s daily AQI was less reliable for predicting health problems during warmer weather months, when pollutants mix more.

The most accurate air-pollution detectors

EPA’s stations are the most accurate detectors. The agency’s site, AirNow, uses these readouts to calculate current AQI. AirNow also predicts next-day AQI by analyzing recent data with sophisticated forecasting algorithms.

Through AirNow, you can learn about regional pollution events like wildfire smoke affecting nearly everyone’s air in wide areas around the monitoring stations. But there aren’t enough of these stations because they’re expensive to build and run. A consequence is that on days without a broadly impacting event—when air quality in a given location is shaped more by local factors like traffic—these monitors can’t tell you as much about many places’ local pollution levels. “Monitors are often lacking in areas that are less populated or have only recently become more populated,” says Loretta Mickley, senior research fellow in chemistry at Harvard University.

Read More: Can Creatine Keep Your Brain Sharp?

PurpleAir’s AQI helps inform you about local pollution. Its online map displays readouts from people’s at-home sensors, better reflecting if a nearby traffic jam or mail truck is spiking fumes, a neighbor starts burning trash, or a local factory releases a smoke plume.

“You can’t predict when these things will happen,” says Adrian Dybwad, PurpleAir’s CEO. “If your kid has asthma, you want real-time, real-close information.” The EPA is piloting ways to combine its official sensors with PurpleAir data.

PurpleAir can be “really useful,” Kelp says, though his research shows its crowdsourced networks rarely include lower-income communities. He also notes the at-home sensors sold by PurpleAir, ranging from $139 to $299, are lower quality than the EPA’s stations—and they become less accurate when misplaced or degrading over time. “There are no standards for installing or maintaining them,” he says.

PurpleAir doesn’t forecast pollution, while AccuWeather tries to predict AQI hourly throughout the day for towns or cities based on available data informing their models. “We focus on quality control as we integrate the latest observations as quickly as possible,” Porter explains. AI plays a role; Porter says AccuWeather’s machine learning algorithms compute 70 billion data points each hour.

A lack of standardization

Another issue is that AQIs use different color codes and thresholds for when the air is bad enough to trigger health problems in a single day. AirNow flags air quality as unhealthy—color-coded orange—whenever PM2.5 levels rise above 35.5 micrograms.

But the WHO’s guidance is more stringent, recommending a maximum of 15 micrograms. AccuWeather’s scale tracks to the WHO standard. This explains why AccuWeather’s AQI might indicate pollution is “fair” when AirNow shows it’s “good.” PurpleAir lets you choose filters that apply either the EPA’s or WHO’s standards.

Read More: Your Quest for Perfect Sleep Is Keeping You Awake

Mickley generally follows the EPA guidance. “I will exercise outside in moderate yellow conditions,” she says. “When it turns orange, I stay inside.”

Thurston thinks color-coded schemes should eliminate green to avoid implying completely safe air, since even the lowest pollution levels compromise health with long-term exposure. For the average concentration of PM2.5 you breathe throughout a given year, lower cutoff points have been established by both the EPA (9 micrograms) and WHO (5 micrograms). This means if your average exposure is regularly above these levels over the long-term, risks for chronic diseases may rise.

How to use air-quality readings in your everyday life

So how should people use all of these different AQIs? “The best approach is to combine them,” Kelp says.

Here’s a five-step plan:

Sign up for AirNow emails

AirNow is the go-to place to learn about regional events significantly driving up pollution. Sign up for its daily emails, called EnviroFlash, to stay informed. For instance, if a wildfire—even if far away—coincides with weather systems blowing pollution into your region, AirNow’s email will recommend staying indoors more than usual.

Follow a local sensor

Before exercising or spending much of the day outside, check the air quality by looking at PurpleAir’s map displaying local sensors, wherever people own and deploy them. Another similar site, like IQAir, might draw from a sensor that’s closer to you.

You could also get your own personal monitor—many are affordable, and though their accuracy is limited, “they’re good for showing overall trends,” Kelp says.

Observe your environment

Learn to recognize generalities and patterns in your environment that, more often than not, track with pollution. Combined with AQIs, they should inform your overall assessment and actions.

For example, Thurston realized pollution is usually higher on the subway, so he wears a mask when riding it.

Read More: You Should Be Washing Your Shoes. Experts Explain How

Khreis knew from research that living by a busy road increased her exposure “exponentially” compared to about 1 mile from the road, even though the available AQIs didn’t reflect this problem. She moved to a home farther away.

She also bikes in areas with less traffic and more greenery. Trees may help disperse pollution. Results depend on several factors like tree species, but “overall I think they help,” Khreis says.

Other patterns are weather-related:

Sunny summer afternoons often coincide with pollution, which then drops in the evenings.

The reverse may be true in winter: higher AQIs occur in the morning as people wake up and turn up their heating units.

Rain droplets may wash away pollutants.

Avoid exercising outside when worse air is likely based on these patterns, or at least check your AQI app beforehand to help ensure pollution isn’t excessively high.

Check hourly forecasts

If you’re about to go outside for a long time, consult AccuWeather’s hour-by-hour forecast. Just don’t over-rely on its accuracy, since it may shift while you’re out. “We always recommend people check back with us to stay updated,” Porter says.

Local monitors can help point you to real-time changes.

Aim for mostly good air

Try to limit your average exposure on most days.

Cumulative long-term exposure to low-level pollution may cause more chronic disease than peak pollution events. So if you’re outside for a while on a day with high AQI, it helps significantly to drop your average by reducing exposure when indoors. Consider getting indoor air purifiers—for your house and car—and an electric stove instead of a gas one, which emits a carcinogen called benzene.

The air outside is often beyond your control, but people spend only 10% of their time there. Cleaning up your own indoor air could be a life-saver.

Leave a comment