As the world strives to get to net-zero emissions, Brazil can play a formidable role in helping to enable such an outcome, but it won’t happen without the broad recognition of carbon removal credits and a trading capacity to shift the credits between countries.

I have recently been in Rio de Janiero, Sao Paulo and Brasilia participating in the launch of a new analysis by the Shell scenario team that is focused on Brazil and looks in depth at the energy transition in the country, but also the enormous potential for managing carbon dioxide on a scale that is globally relevant. That analysis or country Scenarios Sketch, Brazil: Leading the world to net-zero emissions (in both Portuguese and English), builds from The Energy Security Scenarios, using the detailed country level data for Brazil that we in Shell have available from our World Energy Model.

Brazil is both unique and fascinating from a carbon cycle perspective, given the size of the rainforest, the large agricultural sector, and the important role that both bioenergy and hydroelectricity play in the country today. As such, this Scenarios Sketch is entirely different to all the others we have worked on, in that it draws heavily on our land carbon analysis work and required a deep dive into the Brazil bioenergy sector.

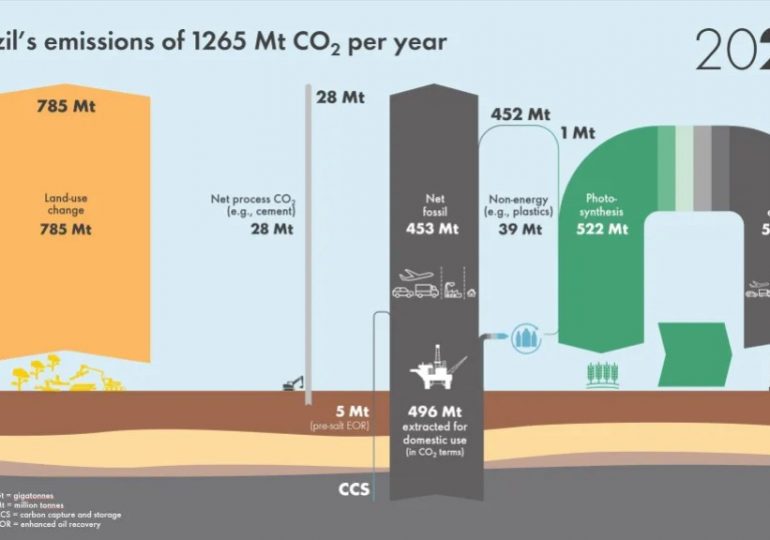

The emissions starting point for Brazil is unlike any other country. Fossil fuel CO2 emissions, primarily from oil, are 453 Mt per year, but significantly less than land use CO2 emissions of 785 Mt per year, largely coming from ongoing deforestation in the Amazon region. Fossil fuel CO2 is also surpassed by the bioenergy system, although that system is effectively carbon neutral. Total CO2 emissions are around 1.3 Gt per year, but total greenhouse gas emissions are just over 2 Gt per year, with the addition of methane and nitrous oxide mainly coming from the agricultural sector.

The Brazil Scenarios Sketch incorporates two scenarios, Sky 2050 and Archipelagos. Both start with the realities of the 2020s, meaning that the energy system and future energy policy landscape are showing real signs of change, but also recognising that an insufficient amount of progress has been achieved on the scale required to reduce emissions substantially by 2030. As time moves on into the 2030s Sky 2050 takes a normative approach that starts with the desired outcome of global net-zero emissions in 2050 and works backwards in time to explore how that outcome could be achieved. By focusing on security through mutual interest, the world achieves the goal and a global temperature rise of less than 1.5°C by 2100. Archipelagos follows a possible path in a world focusing on security through self-interest. Even so, change is still rapid, and the world is nearing net-zero emissions by the end of the century but the temperature outcome in 2100 is a plateau at 2.2°C.

In the context of Brazil, while the energy transition takes some interesting twists and turns, the initial focus in Sky 2050 is on ending deforestation. In the scenario this is achieved in the early 2030s through a concerted government effort, in combination with the existing efforts through the voluntary carbon market. Government-to-government partnerships flourish and support the effort as countries outside Brazil recognise it is in their interests to see deforestation end such that Brazil can move into a phase of bona fide carbon removal through land-use change.

This achievement sets the scene for significant reforestation efforts driven by carbon markets, as the global demand for carbon removals ramps up and compliance markets, such as the EU Emissions Trading System, open their systems to an inflow of removals from outside their domestic boundaries. The important dynamic that results from ending deforestation is a leap in confidence that land-based credits from Brazil now represent true carbon removal and questions on additionality, that have hampered the avoided deforestation credit market, are put to rest.

Not content with land-based removals, in Sky 2050 Brazil sets about developing a CCS industry, starting with the many ethanol plants in the Sao Paulo region where the prospects for geological storage of CO2 look good. The fermentation of sugar to produce ethanol releases CO2 in pure form which can be captured and geologically stored. Further, the combination of bioenergy production or use with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) delivers permanent removal of CO2 from the atmosphere.

In Sky 2050 in CO2 terms, by 2040 Brazil is already in a net-drawdown position, with a complete turnaround in land-use emissions and a CCS industry well established and storing over 50 Mt CO2 per year.

As the transition proceeds in Sky 2050, Brazil also reaches net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. But doing so requires considerable investment in CCS and mechanisms to incentivise landowners and the agricultural community to adopt new practices and change behaviours. In Sky 2050 a good proportion of these investments and incentives come through the carbon market, both from the domestic emissions trading system and projects channelled through Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Importantly, Brazil has sufficient space in its carbon budget to allow for international trading of removal credits.

Picturing Brazil from an emissions trading perspective in the early 2030s, it might look like the illustration below. There are many potential counterparties, but the illustration imagines the EU ETS and the aviation sector as two potential partners. In Europe the EU ETS (I) will reach a point of zero new allowances by 2040, so by the 2030s industrial concerns could already be feeling the pressure given the lack of immediate abatement opportunities. In the aviation sector in the 2030s, technical solutions (e.g. SAF, e-fuels, hydrogen) for abatement will take decades more to fully implement, so carbon removals are the only short to medium term option.

By 2040, say, Brazil could be supplying significant volumes to these counter-parties but not compromising its own net-zero ambitions. A similar story could emerge domestically through the implementation of the planned emissions trading system.

Importantly, trade in carbon removals can bring investment and income into the Brazilian economy. But much of the story depends on a fully functioning Article 6 and a willingness by regions such as the EU to make use of it. To date, the signs pointing to such an outcome have been limited, despite some effort by the Article 6 negotiators at UNFCCC meetings.

The Brazil Scenarios Sketch provides many energy and greenhouse gas insights into a vibrant country with an interesting story to tell. You can find that story here.

Leave a comment