In this week’s blog post we’re discussing tackling climate change through 15 years of community-led exploration of underwater kelp forests. Carolina Olguín Jacobson, author of “Recovery mode: Marine protected areas enhance resilience of invertebrate species from marine heatwaves”, shares insight into the effects of heatwaves on kelp-related species and how monitoring and conservation efforts like Sirenas de Natividad and the Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) of Mexico, may be the solution to managing heat stress in observed marine organisms. Through her incredible research, Carolina shares the wonder of discovering (or rediscovering) our Earth’s oceans and reminds us not to be afraid to dive in on the deep end.

A Spanish translation of this blog post is available here.

About the paper:

Imagine your town was suddenly hit by an extreme heatwave, not for a few days, but for months or even years. And imagine you couldn’t escape it. That’s the reality marine organisms face during marine heatwaves (MHWs) — prolonged periods of anomalously warm ocean temperatures. These events are becoming more frequent and intense due to climate change, pushing marine ecosystems to their limits, especially species that can’t move away or seek deeper waters to find cooler temperatures.

In our study, we examined how the 2014-2016 MHWs, the strongest and longest MHWs ever recorded in the Northeast Pacific Ocean, impacted kelp forest communities, and assessed whether marine protected areas (MPAs) helped these species resist and recover from these extreme events. Our research focused on Isla Natividad, a small island off the coast of Baja California Sur, Mexico. There, the local fishing cooperative, called Buzos y Pescadores de la Baja California, holds exclusive fishing rights and are responsible for enforcing local management and regulations. In 2006, they voluntarily established two no-take marine reserves.

Our findings showed that while marine reserves couldn’t fully prevent the impacts of the MHWs, they did boost resilience for some key invertebrate species. Sedentary species like abalone and turban snails not only better resisted the heatwave inside the reserves, but they also recovered faster! In fact, abalone biomass inside the reserves quadrupled in the years following the heatwave, something we didn’t observe in the fish community or in more mobile species such as spiny lobsters.

The main take home message was that these results have an impact beyond Isla Natividad. They suggested that MPAs, especially when well-managed and tailored to species with localized movement patterns, can be effective tools for climate adaptation. Although the benefits are species-specific and not universal, marine reserves remain a key strategy for building resilience in warming oceans.

About the research:

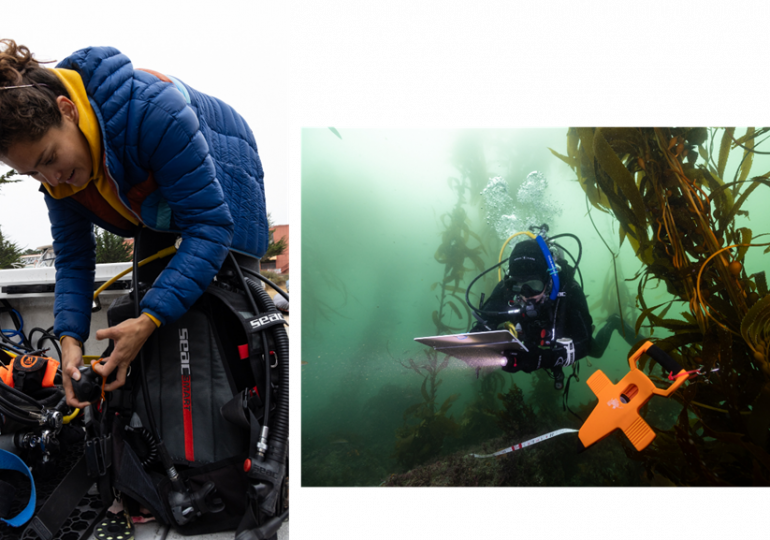

One of the most valuable aspects of our study is the dataset itself: 15 years (2007–2021) of long-term ecological monitoring made possible through a unique collaboration between the local fishing cooperative of Isla Natividad, the Mexican NGO Comunidad y Biodiversidad A.C., and Stanford University. People often underestimate what 15 years of data truly represent. But think back—where were you 15 years ago? How much has changed since then? That’s the kind of depth and perspective this research offers. When the cooperative established the two no-take marine reserves in 2006, several male fishers received training to conduct the underwater surveys. This group has evolved since then, in 2013 two women joined the monitoring team, and by 2019 the group “Sirenas de Natividad” (mermaids from Natividad) was officially formed. Today, five women lead and coordinate the kelp forest monitoring on the island. Sirenas de Natividad are now expanding, inspiring other women in fishing communities of Mexico.

Since 2006, the cooperative has conducted annual surveys inside and outside the reserves generating an invaluable long-time timeseries that allows us to detect ecological changes, understand species responses to extreme events and assess the effectiveness of marine protection over time. I cannot emphasize enough the importance of sustained monitoring across ecosystems, multiple taxa and regions, without this kind of long-term data we would miss the signals of resilience and change in a population.

What surprised us most was the remarkable difference in recovery among species. While we expected some benefits from the reserves, we didn’t anticipate such a strong and sustained rebound in abalone after the heatwaves. This outcome provides new evidence on the efficacy of MPAs as climate adaptation tools and shows that marine reserves can indeed bolster resilience for some species following climate-driven disturbances.

Looking ahead, our next step is to evaluate whether similar patterns exist in other marine reserves along Baja California Peninsula. We want to compare ecosystems and management approaches, and to better understand the ecological traits and mechanisms through which marine reserves may confer climate resilience.

About the author:

My journey as a biologist began with studying the taxonomy of sea cucumbers during my undergraduate degree at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). After that, my focus shifted to a broader marine aspect. For my Master’s, in La Paz, Baja California Sur, I researched the effects of different temperatures on jellyfish. Then, pursuing a lifelong dream, I moved to Australia for my PhD, where I continue working with jellyfish but investigating the impacts of pesticides on the different life history stages.

After completing my PhD, I wanted to strengthen my fieldwork skills. I am now a postdoctoral researcher at Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University, focusing on kelp forests ecosystems, marine reserves and small-scale fisheries. I also co-established MasKelp foundation, an NGO that aims to understand and protect kelp forests in Latin America. I’ve been trained to identify and monitor fish and invertebrates in kelp forests and have worked closely with fishing communities to monitor a network of oceanographic sensors. I feel incredibly fortunate to explore such remote and beautiful places to conduct underwater surveys. If I could give a piece of advice to my younger self, it would be “don’t be afraid to switch fields if your interests evolve, there’s a world of incredible things to discover.”