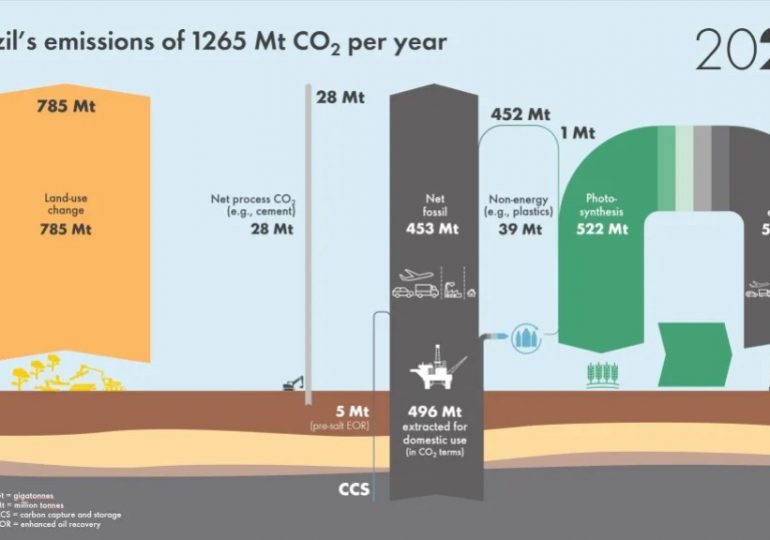

The recent release of the Brazil Scenarios Sketch, based around the Shell Energy Security Scenarios, highlights the role that land-use change could play for Brazil to achieve two important outcomes; reaching net-zero CO2 emissions within its domestic economy and becoming an important supplier of carbon removal units into the global economy as the world strives to balance carbon emissions and reach net-zero. In fact, these two outcomes are inextricably linked.

The CO2 emissions starting point from Bazil is shown in the illustration below, with land-use change being the largest component of the story, eclipsing fossil fuel emissions and even exceeding the large bioenergy CO2 loop.

Within the scenarios team in Shell, understanding and accounting for land emissions has become a core component of the modelling expertise that has been developed. It is approaching the level of detail that is used in energy system modelling, although the uncertainty related to land-use emissions is much greater than that associated with energy system emissions. Nevertheless, by using a consistent data focused approach, clear trends emerge, and conclusions can be reached relating to changes of direction.

In Brazil, the 785 Mt CO2 emissions shown above come mainly from ongoing deforestation. However, there are contributions from other ecosystems which are under threat. The breakdown is shown below and illustrates the detail available in the scenarios land-use database, which includes nearly twenty different land-use change types. While the categories are referenced by ecosystem type, the fact that they are shown as net positive emissions means that degradation is underway.

The scenario storyline for Brazil features two scenarios, Sky 2050 and Archipelagos. Both start with the realities of the 2020s, including the struggle to end deforestation in Brazil. As time moves on into the 2030s Sky 2050 takes a normative approach that starts with the desired outcome of global net-zero emissions in 2050 and works backwards in time to explore how that outcome could be achieved. By focusing on security through mutual interest, the world achieves the goal and a global temperature rise of less than 1.5°C by 2100. Archipelagos follows a possible path in a world focusing on security through self-interest. Even so, change is still rapid, and the world is nearing net-zero emissions by the end of the century but the temperature outcome in 2100 is a plateau at 2.2°C.

Both scenarios incorporate significant shifts in land-use policies and practices in Brazil. These are partly driven by government and incentive structures, but also driven by necessity and the recognition across society in Brazil that the threats emerging from ongoing deforestation, such as biodiversity loss and changes in South America rainfall patterns are unsustainable in the shorter term.

In Sky 2050 there is global recognition that Brazil holds the keys to net-zero emissions for many countries, in that the potential for natural carbon removals coming from Brazil can balance ongoing emissions in scores of economies. This leads numerous countries to invest in actions in Brazil to end deforestation, an essential first step towards delivering credible carbon removal credits from reforestation. In the scenario Brazil still overshoots its 2030 goal to end deforestation but has certainly achieved the goal by 2035. By then reforestation activities are becoming extensive with some 4 Mha of land under project management.

In the second half of the 2020s in Sky 2050 the agricultural sector adopts sweeping reforms, driven by a clear financial incentive structure underpinned by both domestic and international demand for soil carbon credits. The use of biochar in farming is taken up, together with changes in cropping and grazing. By 2030 these three new practices are drawing down 34 Mt of CO2 per year, or about 10 Mt of carbon added to the soil, which in turn means improvements in farm output. The carbon credits produced by the farmers are sold into the domestic emissions trading system or transferred out of Brazil to other countries via Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. In 2030 farm income is bolstered by well over $2 billion as a result.

Biochar use has a long history in Brazil. Analysis of soils has revealed that more than 2,000 years ago, Amazonian Indians used to bury stable carbon in the soil. A mixture of broken pottery and various other organic materials has maintained the high fertility potential of these areas to this day. Biochar production is a technique through which carbon from biomass is transformed into stable carbon that can be captured in the soil. In addition to this long-term carbon sequestration role, biochar is also beneficial to soil performance as it improves the retention and diffusion of water and nutrients. Biochar is a soil additive produced through pyrolysis, a process that involves heating biomass waste (manure and agricultural residues) at high temperature in an oxygen limited environment.

By 2050 in the Sky 2050 scenario, Brazil is drawing down nearly 700 Mt of CO2 through nature-based removals, with reforestation and agricultural biochar practices accounting for well over half the amount. But changed grazing and cropping practices as well as forest management and agroforestry also play important roles. The role of carbon markets acting as a conduit for international financing of domestic actions in Brazil cannot be understated. Without a global demand for carbon removals, the nature-based project investment required and incentives paid out to farmers cannot emerge on the scale necessary for Brazil to make all the changes that the scenario imagines.

In the Archipelagos scenario self-interest prevails globally. As a result, Brazil is not presented with the same level of partnerships or the major global demand for carbon removals. The result is that the country doesn’t end deforestation, although by mid-century the practice has been halved and the net-CO2 impact is zero as reforestation and forest management activities balance the losses still being seen. Agricultural practices do change in Archipelagos, but with the global voluntary market being the primary driver of change rather than a mixture of voluntary and compliance markets, progress is slower than Sky 2050. However, the same endpoint is eventually reached, albeit one to two decades later.

In both Sky 2050 and Archipelagos the changes that Brazil can deliver in land-use practices mean that net-zero CO2 emissions in the country is quite possible, coming a decade either side of mid-century with Sky 2050 delivering the outcome more rapidly. In both cases fossil fuel emissions have been reduced by some 20% when net-zero CO2 emissions is achieved, but that reduction is far from being the major contributor to the outcome.

Note: Shell Scenarios are not predictions or expectations of what will happen, or what will probably happen. They are not expressions of Shell’s strategy, and they are not Shell’s business plan; they are one of the many inputs used by Shell to stretch thinking whilst making decisions. Read more in the Definitions and Cautionary note. Scenarios are informed by data, constructed using models and contain insights from leading experts in the relevant fields. Ultimately, for all readers, scenarios are intended as an aid to making better decisions. They stretch minds, broaden horizons and explore assumptions.

Leave a comment