This is a guest blog post. All opinions are that of the guest blogger.

The year 2024 saw a resurgence in the United States in the use of ballot initiatives by farmed animal advocates. In Sonoma County, California, a coalition led by Direct Action Everywhere (DxE) proposed an outright ban on Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs)—a term used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that can be interpreted as defining factory farms—which would have resulted in the closure of 21 factory farms. In Denver, Colorado, the newly formed organization Pro-Animal Future (where I hold a leadership role) ran a measure banning slaughterhouses, which would have shuttered the largest lamb slaughterhouse in the country. Although these measures (along with a fur ban initiative in Denver) failed, I believe they were some of the most exciting and promising new campaigns for animals last year. In this post, I will share what I believe are the most important lessons learned for running ballot initiative campaigns and how Pro-Animal Future will apply these lessons to carry this campaign strategy forward.

What Are Ballot Initiatives?

Ballot initiatives (also known as citizen initiatives or ballot measures) are laws written by and voted on directly by citizens. They are a somewhat unique legal instrument available in only a handful of countries around the world. To create one, a group of citizens write a piece of legislation, collect signatures from registered voters in the relevant jurisdiction, and, if they meet the threshold for the number of signatures required in the allotted time, cause the proposal to be voted on in a general election. In most cases, a simple majority vote will allow the measure to become law. In the U.S., ballot initiatives are possible at the city, county, and state levels in about half the states in the country.

Ballot initiatives have represented some of the largest victories for animal advocates in recent decades—most notably Prop 12 in California, which banned the production and sale of animal products from suppliers that use extreme confinement (e.g., battery cages and gestation and veal crates). Inspired by the decisive victories of welfare measures like Prop 12, advocates sought to push the envelope further last year. In important ways, these 2024 initiatives represented a departure from previous strategies. Where measures like Prop 12 sought to implement common-sense incremental welfare reforms,1 the two initiatives discussed here aimed to trigger a more fundamental reckoning with the industry responsible for cheap meat. In this regard, they more closely resembled the Swiss citizen initiative from 2022 that sought to ban factory farming nationwide. The Swiss electorate voted against this measure, 63% to 37%.

Why Ballot Initiatives Are Important

The ballot initiative process creates several unique opportunities for animal advocates. My own interest in ballot initiatives was originally sparked not because of the ability to pass laws but rather as a way to shift our movement’s engagement with the general public.

Recognizing the limitations of the traditional focus on individual consumer change (i.e., “go vegan”), a few of us decided to step back from frontline advocacy and design a research project to understand what it would take to escape the limitations of the consumer frame of advocacy. That project was called Pax Fauna—over two years, we conducted an extensive study of public opinion involving 200 hours of interviews with nearly the same number of regular meat-eating Americans.

We found that, while some animal advocates had started pivoting from a “go vegan” message to calling for “systemic change,” the phrase systemic change meant basically nothing to the general public. In fact, without a clear mechanism for how citizens could participate in a gradual, collective transformation of the food system, they would default to filtering animal advocacy messages through the consumer lens, which in turn generated hostility to advocates’ goals.

The key, we discovered, was to provide our audience with opportunities to act through a civic frame, where consumer values of individualism are replaced with a voter role characterized by collective action. In other words, rather than asking individuals to make a big change all at once by going vegan or vegetarian, we can ask them to support collective civic action by voting for stronger welfare regulations or even for policies that will catalyze a transition away from animal farming.

Framing Matters

Consumer framing: Public hostility

Systemic framing: Public confusion

Civic framing: Ballot initiatives create collective action opportunities

This insight clearly pointed towards ballot initiatives, as they are the most direct way our movement can engage the public in the conversation about factory farming with their voter hat on. We soon saw several other reasons to be excited about pro-animal ballot initiatives. Compared to the conventional legislative process, voters are often more willing to entertain transformative proposals than the politicians they elect to represent them. For example, in Florida in 2020, the same electorate that voted by a margin of 51% to 48% for Donald Trump over Joseph Biden for president also voted 61% to 39% to pass a large minimum wage increase to $15/hour, a policy to the left of most national Democratic officials. This discrepancy shows how voters often act independently of their usual partisan identity when presented directly with ballot questions.

Another piece of Pax Fauna’s research pointed to a different need ballot initiatives could fill. In a study of current and former animal rights organizers (people who dedicated massive amounts of time and energy to the movement in an unpaid capacity), we found that the leading cause of burnout was likely disillusionment about whether one’s work was making a difference. The grassroots movement, while holding enormous potential to get work done, was in dire need of concrete victories to work towards and celebrate.

In summary, the strategic opportunities that drew us to ballot initiatives were:

to turn factory farming into a political (rather than consumer) issue and engage the public in their role as voters, where collective values are more prominent;

the opportunity to pass bolder laws that elected officials (more subject to lobbying pressure) would be unwilling to touch;

to provide tangible wins for activists to work towards while gradually building public support so that even a losing campaign is bringing us closer to eventual victory.

The Campaigns

In early 2023, Pax Fauna incubated a new social movement organization called Pro-Animal Future (PAF), which is dedicated to creating a scalable model for grassroots ballot initiative campaigns. Pax Fauna’s research also inspired our friends at DxE to experiment with ballot initiatives. Both organizations were seeking to strike a delicate balance; we wanted a campaign that had a real chance of winning, but also a policy that would challenge public opinion merely by being introduced. We wanted to know: if 63% of voters would support a ban on intensive confinement, what’s the most transformative thing that 51% of voters would support?

Since both groups decided we weren’t quite ready for a statewide campaign, we chose to run pilot campaigns in progressive counties that might be ripe for even bolder initiatives. DxE chose a factory farm ban in Sonoma County, a liberal region with a very strong identity around humane farming. PAF chose the slaughterhouse ban in Denver, a progressive urban county where most voters would be surprised to learn an industrial slaughterhouse still exists.

Both groups also ran companion measures that were expected to sail through with relative ease. DxE duplicated the CAFO ban in progressive Berkeley, where it scared a horse racing track that technically met the definition into shutting down before the vote even took place. PAF simultaneously ran a fur ban in Denver that was intended to serve as a foot in the door with voters, hopefully increasing support for the slaughterhouse ban.

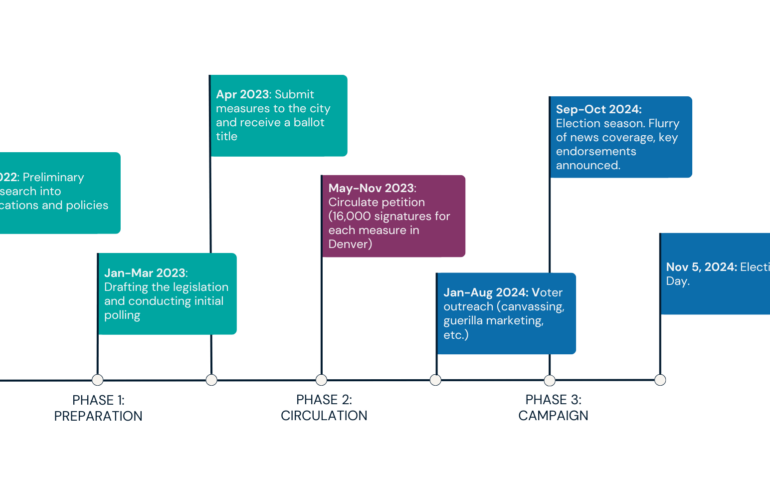

Project Timeline

Taking PAF’s campaigns in Denver as an example, here is the basic timeline of a ballot initiative campaign:

Crucial Wins

Despite the worse-than-anticipated losses, there are several reasons to celebrate these campaigns and even more reasons to double down on the strategy. Applying the hard-won lessons of 2024, animal advocates are poised to use ballot initiatives to shake things up like never before.

Mobilization

Over the course of 18 months, PAF’s campaigns mobilized nearly 200 local activists—not counting another hundred activists who traveled from around the country or joined remote phone banks to be part of the campaign. We collected 32,000 signatures without paying a penny for paid circulators. We conducted thousands of person-hours of outreach on doors, phones, and in crowded public areas, reaching well over 20,000 people with direct peer-to-peer outreach. We also wheatpasted over 7,000 educational posters around the city—anecdotally, we heard from far more voters who had seen our posters than had spoken to an activist directly. Many thousands more were reached through banner drops at busy intersections or overpasses. All of these actions describe our field operation or outreach done by activists. (I’ll discuss mass communication channels in the next section.)

In a city the size of Denver (less than 10% of the population of New York), I have almost never seen any other type of campaign create sustained mobilization on that level, and certainly not reach so many ordinary people. Uniquely, as the election drew nearer, citizens started actively approaching our canvassers to ask about the campaigns. The discussion around the ballot initiatives drew the public towards us and drastically altered the tenor of our conversations compared to generic vegan outreach. Even if you were to remove the ballot initiatives from the picture while finding some other way to generate the same level of mobilization, I do not know of significantly more effective activities a mass volunteer base could have engaged in.

Now the catch. While this campaign engaged more activists than anything I’d previously done after organizing for years in the same area, the average lifespan of those activists was not longer than what I’d seen previously. While we hoped that a clear, definite end goal would keep activists engaged and prevent burnout, I couldn’t say that panned out this time. Indeed, we originally imagined that one of our primary goals of county-level campaigns would be to build up an army of activists across the state over years, so that when we launched a statewide campaign (requiring 10x the number of signatures in the same amount of time), we’d already have enough people ready to hit the streets. So far, that hasn’t materialized. While we’ve built a strong leadership bench of a dozen or so experienced and highly dedicated volunteer leaders who I expect to stay engaged, it appears for now that we’ll have to largely rebuild the activist community for our next campaign in the same region. As a young organization, we’ll definitely be experimenting with ways to increase volunteer retention, but in the 10 years I’ve spent embedded in different grassroots organizations in the animal and climate sectors, activist churn has been more or less constant. I no longer believe we should build a model that relies on changing that.

Salience: Why Ballot Initiatives Lose Forward

As a direct result of PAF’s campaigns, animal rights and factory farming were far-and-away the top local political issues in Denver in 2024. This was a result of the field outreach described above combined with dense local media coverage arising from the innate relevance of the measures to the public; every voter was going to have to decide how to vote on these issues, so every local news outlet ran several stories and op-eds each about them. Paid ads for the measures on social media, billboards, and podcasts garnered unusually high engagement for the same reason. In the end, the local government mailed a question about animal rights to every voting household in the city, over 350,000 voters wrestled with whether to ban slaughterhouses, and 120,342 of them (the vast majority being meat-eaters) voted in favor.

While voters ultimately went against both Denver measures, there is good reason to think the campaign brought huge numbers of people closer to our camp. To start, simply shifting the issue from the consumer lens to the civic lens expanded our support base from at most 5% to 10% vegans and vegetarians to 36% pro-animal voters. Political and media institutions were united against the bans, but even the main opposition spokespeople were forced into a defensive posture—their message was not “There’s nothing wrong with industrial slaughterhouses,” but instead, “Yes, this is a problem that needs to be addressed but this measure isn’t the right way to do it.”

The opposition will always nitpick or invent problems with the way a measure is worded to sow enough doubt to get a No vote. While this poses a general challenge for ballot initiatives, it also points to why ballot campaigns can be a great strategy for losing forward. Indeed, examples from the recent history of forward-losing ballot initiatives were a major part of the inspiration for our campaigns. Take cannabis legalization as an example. The first cannabis legalization initiative to get on a statewide ballot was in California in 1972. It failed 33% to 67%. Similar measures popped up around the country in subsequent decades. Starting in 1998, there was a statewide legalization proposal on the ballot in at least one state (often two or three) in every even-numbered election year. Each one was defeated until 2012, when suddenly, four out of six were successful, opening a floodgate of cannabis legalization laws continuing through to today. Hindsight makes it clear that these losing propositions thrust the issue into the national political discourse and facilitated a gradual shift in public opinion that eventually culminated in victories for legalization advocates. The recognition of gay marriage followed a similar path in the U.S., as did women’s suffrage a century earlier, both propelled forward by failed ballot initiatives.

In Denver and Sonoma County, the factory farm industry’s own messaging, while securing a short-term victory, has exacerbated their vulnerabilities and exposed them to anathematic public scrutiny. We can and should press the advantage by doubling down.

Hard-Won Lessons

In choosing a campaign that would have a chance of passing while putting maximum pressure on the industry, we sought to draw out the very best from both ourselves and our opponents. We wanted to give this campaign everything we had to ensure we learned the most, and we wanted our opposition to give everything they had for the same reason. Now, we’ve forced the industry to show its cards. We know what messaging and tactics they will use in response to existential threats, and we have years to prepare to counter their best messaging while learning from their best tactics. That might be the most valuable win of all. Let’s look at some of those lessons in depth.

We Can’t Ignore Traditional Power Centers

Before launching these campaigns, we thought that ballot initiatives represented a chance to completely bypass the corrupt traditional political process, where we could never compete with the industry’s vast war chest of lobbying money. We learned the hard way that things are not so simple. In reality, political gatekeepers still exert significant influence over the politics of direct democracy. These include political parties, elected officials, media corporations, prominent lobbyists, and even ostensibly apolitical institutions like public universities.

The first warning that we had underestimated the importance of institutions came in May 2024, when Colorado State University (CSU), home to one of the largest agricultural colleges in the country, published an economic analysis from four industry agents forecasting wildly inflated economic impacts from the closure of a single mid-sized slaughterhouse. While we’d been focusing on reaching voters directly, our opponents had been lining up institutional allies; this was the first to drop. From that moment on, the CSU study shaped almost all media coverage decisively against us. Soon after, we heard grumblings from what would turn out to be the first of several city council members to actively oppose both measures. We had completely neglected to reach out to the city council, thinking that few Denver voters could name even a single member of the council and thus wouldn’t be influenced by their endorsements. This was true, but the council members had other ways of influencing the process, including through their relationships in the media, that would indirectly impact voters.

Throughout the month of September, every key endorsement broke against us: The Denver Post (the local paper of record), the mayor, the Democratic Party, and several unions (despite the facility not being unionized). The culmination of this institutional backlash came on September 21, about six weeks out from the election, when the Central Committee of the Denver Democratic Party voted 207 to 12 to formally oppose the slaughterhouse ban. (The vote on fur was nearly as lopsided.) Even the independent progressive organizations forming the left flank of the Democratic coalition (e.g., Democratic Socialists of America, Working Families Party) either took no position or actively opposed. For us, all of this appeared to come out of the blue. Only when the dust settled after the election did a clear picture emerge.

Power Is for Sale: How Industry Lobbyists Bought Every Key Endorsement

The largest factory farm lobbying groups in the country spent over $2 million fighting the slaughterhouse ban, a win in itself and a demonstration of how seriously they took the threat. (The same amount was spent fighting the Sonoma County CAFO ban.) However, as we looked more closely at how they spent this money (all campaign expenditures must be reported to the city elections office), a confusing pattern emerged. They spent over $600,000 hiring practically every lobbying firm in Denver, along with several more from farther afield. Why, we asked, are they spending a third of their budget hiring lobbyists when the vote will be decided by ordinary voters? They spent another third on expensive campaign consultants, who basically add a massive upcharge to campaign services like mailers, texts, and yard signs that can be done much more cheaply (and just as well) in-house. And they blew hundreds of thousands of dollars sending mailer after large, expensive, full-color mailer to Denver households, as many as eight to a single household, despite abundant evidence that repeated spending on the same communications channel is ineffective. At first, we felt consoled: clearly (we told ourselves), they’re squandering all their money on an ineffective campaign.

Clearly not, I had to admit, on election day. But it was only weeks later that the curtain was pulled back for us. We met with a friendly lobbyist who explained to us how the economy of local politics really works:

Say you have held elected office in Denver for 10 years. You’ve met and worked with everybody who matters in local politics. From all your campaigns, you’ve built up name recognition and a sizable email list of politically engaged citizens. When you decide you’re done running for office, you cash in by setting up a “pay to play” shop, a consultancy focused on a single niche aspect of political campaigns—yard signs, mailers, press relations, etc. From there, it’s essentially an extortion racket: If you hire their firm to service your campaign, they’ll put all their insider relationships, name recognition, and email list to work for you. That’s the real product. And if you don’t hire them, they’ll direct all of it against you so that next time, you’ll have no choice but to hire them. Everybody who has enough influence to be worth hiring sets up a shop like this.

The Democratic Party endorsed against the measures because all the important decision makers in the party had either been bought off this way, or were getting their phones blown up by people who had. Same goes for city council and The Denver Post. Even DSA—the rank and file were poised to recommend a vote in favor of the slaughterhouse ban, but the leadership got phone calls from all the people they need to have good relationships with to do the work they care most about—union leaders, electeds, other gatekeepers. The message was clear: You cannot support this measure. So they took it off the agenda, and the vote never happened.

Ultimately, this lobbyist estimated that on an issue such as this where most voters don’t have preformed ideas, the Democratic Party endorsement in Denver would swing the results by at least 20 points in either direction, meaning that all this back-channel politicking likely secured the result for our opponents. This means that while voters are sometimes willing to buck their party affiliation on direct ballot questions, they need a fair amount of persuading. A campaign that outmaneuvers its opponents in enough categories could still overcome party endorsements, but they will likely be one of the most important contests for any pro-animal ballot initiative.

The fact that our opponents spent well over $1 million just on this strategy when our entire campaign budget was closer to $300,000 clearly presents an obstacle for our movement. It is not, however, an insurmountable one. I now believe shifting even $50,000 away from paid ads and towards greasing palms this way would make a sizable difference. But there’s an even more effective way we can do battle on this front: by putting our advantage in people up against their advantage in money. In fact, here’s how we had already started doing this in 2024.

The Electoral Game Should Come First

As a result of PAF’s pilot campaign in Denver last year, we’ve made enemies in the city council, the Democratic party, the local media, and various NGOs (unions, restaurant associations, etc.). While these relationships are far from irreparable, it was a rough start. But this wasn’t our only pilot campaign in 2024, and the other provides a sharp contrast.

In Portland, Oregon, we tested out a different form of political campaign for animals: voter bloc organizing. Instead of starting with a ballot initiative (still our ultimate objective), we entered the Portland political scene by sending city council candidates a questionnaire about pro-animal policies, and offering endorsements (along with volunteer canvassers and bundled donations) to the ones who responded enthusiastically. Instead of a pesky upstart, PAF’s reputation in Portland is of a savvy political faction that everybody wants to be introduced to, and for a small fraction of the work and an even smaller fraction of the cost. With the final results tallied, five out of 12 members on the new Portland City Council are PAF endorsees who have committed to supporting a range of policies from default veg municipal procurement to bans on fur, foie gras, and rodenticides.

While any of these wins would be important, we are a long way from truly transformative policies, like a factory farm ban, being passed through the conventional legislative process. However, even if our focus is on bringing those more transformative policies through ballot initiatives, we can now clearly see the importance of embedding ourselves in the local political ecosystem first, and the voter bloc strategy is the perfect way to do that. If we had effectively organized around a city council election in Denver before launching our first ballot initiative, it’s possible that the relationships developed and favors owed would have been enough to counteract our opposition’s vast spending on lobbying.2

Narrative Is King

Our opponents outspent us 8:1, but that money might not have mattered if they hadn’t spent much of it putting a single concise, persuasive narrative in front of voters over and over again.

In our case, that narrative was jobs. Through paid ads and well-curated news stories, Denver voters were bombarded with images of two or three employees who have worked at the slaughterhouse for decades and risen from humble janitors to upper management. Never mind that such cases are almost unheard of—it was a simple, effective narrative, and they drove it home with gusto. They made better use of visuals than our campaign did, despite what should be a natural advantage for us, given the visually shocking nature of animal abuse in slaughterhouses. In that respect, it actually harmed us that there was only one slaughterhouse in the city. Journalists and politicians dismissed statistics about slaughterhouses in general and insisted on assuming the best when stats weren’t available for this particular facility.

A related secondary narrative was that of white activists imposing their will on an underprivileged Latino community who never asked for the slaughterhouse to be banned. It was small consolation when, after all the votes were tallied, the only precinct in the city to vote in favor of the ban was Globeville, the very same working class Latino neighborhood where Superior Farms’ slaughterhouse is located! Meanwhile, the wealthiest neighborhoods (with names like Denver Country Club) voted against us by the widest margins.

A map of Denver precincts showing that only the neighborhood home to the slaughterhouse voted to close it.

This drives home the point that narratives don’t need to be based in reality to be effective. But I doubt animal advocates can do anything with that information. Rather, this was a story of a vicious double standard. Every claim we made was put through the wringer, even when we had documentary evidence. When we published an undercover investigation of the slaughterhouse a month before the election, some journalists refused to believe the footage was from Superior Farms despite the company not even denying it. (Of course, the footage did come from the facility). Yet their most outrageous claims were laundered by the press. I believe this was largely an extension of the sections above describing how they effectively purchased influence and connections. And much like political influence, as long as we can’t match their spending, we need to find a way to use the resources we do have to build up relationships with journalists and other influencers over time. For instance, looking back to the CSU study, our movement does have some friends in high places, and for our future campaigns, we can ensure we are first to the punch with credible impact analyses that at least deny our opponents narrative hegemony.

What’s Next

Across the board, the 2024 vote totals were lower than we expected. However, all the factors that first made ballot initiatives appeal to us as a strategy apply just as much today. All that’s changed is our level of experience. These campaigns proved that ballot initiatives can mobilize high numbers of activists and force crucial public conversations about animal farming. With the lessons we’ve learned, we’re in a great position to turn these into more effective campaigns and build towards transformative wins. The biggest question facing us now is whether the most direct path there is through notching up wins with more modest campaigns, or continuing to push the envelope and fail forward with campaigns that challenge public opinion.3

PAF is already working on expanding to new cities for our next wave of campaigns in the 2026 election cycle, where we hope to explore that question. In at least one jurisdiction, we’ll be focusing purely on a more winnable campaign (possibly a repeat of the fur ban in Denver with new exemptions designed to reduce opposition.) And in at least one other jurisdiction, we’ll be running a measure designed to shut down some factory farms, ensuring we keep the industry engaged in a life-or-death struggle and seizing all the learning opportunities that will bring.

In each case, we’ll be rolling out our new and improved campaign model: building relationships with local political players well in advance of launching measures; developing stronger messaging backed by credentialed economic analysis; and growing our base of voters, volunteers, and small donors who will power these campaigns.

The path to ending factory farming runs through the ballot box. While the industry may have won this round, they were forced in the process to show their hand—and their fear. They spent millions fighting county-level measures, proving just how threatening they find this strategy. With each campaign, we learn and grow stronger. If we refuse to be deterred and make the most out of every lost battle, victory is only a matter of time.

Further reading

You can read more of Aidan’s blogs on Pax Fauna’s website.

Follow Pro-Animal Future on their website and social media.

Almira, the campaign leader behind DxE’s ballot initiatives in Sonoma County and Berkeley, and Aidan were interviewed on the outcome of their respective campaigns on an episode of the podcast How I Learned to Love Shrimp.

For example, a former strategist from the Humane Society of the United States explained that they would never introduce a ballot initiative if initial polling showed less than 60% support.

For more on this strategy and to start using it in your city, to which there are far fewer barriers than running a ballot initiative, see Get Political for Animals by Julie Lewin.

To complicate this further, many of us feel we’d have had a good shot of winning one or both of the Denver initiatives if we had already known everything we learned over the course of the campaign–and we all agree we wouldn’t have learned as much from an easier campaign.

Leave a comment