In June the Shell Scenarios team launched our Brazil Scenarios Sketch, a deep dive into how the energy transition might unfold in Brazil and how the country can become a world leader in better managing carbon. Since then, the team has been busy sharing the scenarios with many groups, both inside and outside Brazil.

The scenario storyline for Brazil features two scenarios, Sky 2050 and Archipelagos. Both start with the realities of the 2020s, including the struggle to end deforestation in Brazil. As time moves on into the 2030s Sky 2050 takes a normative approach that starts with the desired outcome of global net-zero emissions in 2050 and works backwards in time to explore how that outcome could be achieved. By focusing on security through mutual interest, the world achieves the goal and a global temperature rise of less than 1.5°C by 2100. Archipelagos follows a possible path in a world focusing on security through self-interest. Even so, change is still rapid, and the world is nearing net-zero emissions by the end of the century but the temperature outcome in 2100 is a plateau at 2.2°C.

The scenarios stories and findings have been very well received, but one element of the scenarios has led to quite fierce (albeit friendly) debate. Of course, the whole purpose of scenarios is to challenge the status quo and the linear trend thinking that can emerge from it, so this debate was always welcome.

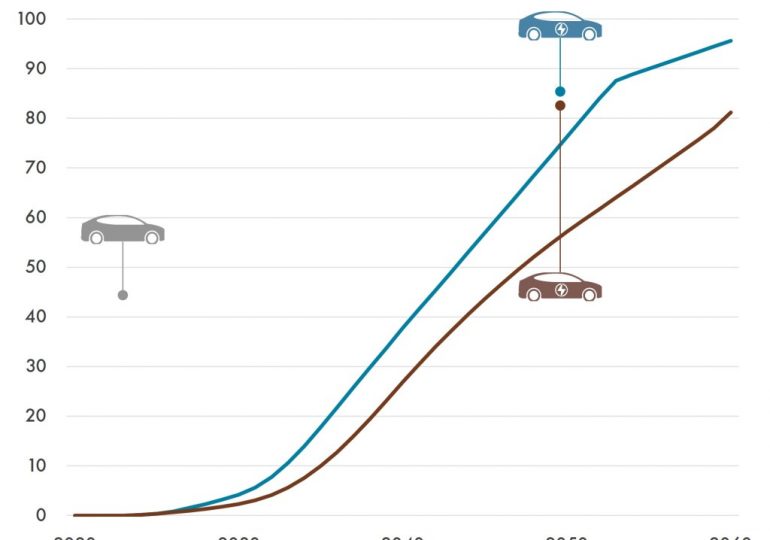

The contentious scenario issue is the speed at which electric vehicles will enter the Brazil market. In both the Sky 2050 and Archipelagos scenarios Brazil is not insulated from a powerful global trend towards electric vehicles (EV), as shown below. By 2050 in Sky 2050 the fleet is nearly 90% electric and in Archipelagos the trend is strongly upward, although by 2050 the fleet is approaching 70% electric. Today, EVs can certainly be seen in Brazil, and I rode in an electric Uber in Sao Paulo, but the numbers are currently small.

In almost every presentation of the scenarios, but particularly those in Brazil, this idea of rapid EV penetration into the Brazil market was challenged, usually in the first audience question. The challenge emerged from the reality of Brazil already having a low carbon footprint vehicle fleet, with sugar cane ethanol dominating the fuel mix today. Typically, the audience was split, with half believing that ethanol was here to stay and the other half agreeing that EVs were the future. However, in one presentation, nobody believed that EVs would make a dent in the market status quo.

So, what’s the story behind our thinking and is Brazil insulated from a global trend towards EVs?

Firstly, it’s important to give some context to the two scenarios, but particularly Sky 2050. That scenario is designed to get to net-zero CO2 emissions globally by 2050 and to do that, all the possible energy transition levers need to be pulled. This includes rapid electrification of the global passenger vehicle fleet, not just to eliminate emissions from fossil fuel use, but also to make biofuels and biofuel feedstocks used for these vehicles available for other purposes, such as sustainable aviation fuels (SAF). Brazil is an important producer of ethanol, so electrification of road transport in the country frees up a considerable amount of biofuel.

However, in Archipelagos, which is a fully exploratory scenario, the same trend of electrification emerges, albeit at a slightly slower pace. The rationale behind this in Archipelagos, but also to attach a plausible narrative to Sky 2050, is one of market forces. There is no indication in Brazil that the government is applying pressure to electrify the vehicle fleet, unlike places such as the EU and UK, so why would it change?

In both scenarios the premise put forward is that the global trend towards EVs is now unstoppable. There will doubtless be hiccups along the way, and we appear to be in a dip now in some markets as purchasing of such vehicles has slowed, but that was equally true for commercial transactions in the dot.com boom in the late 1990s, with the second coming in the 2000s bringing with it a tsunami of change. The EV market has brought with it a number of new entrants, something that the incumbents in the conventional vehicle market were perhaps not expecting. These companies are entering markets such as Brazil; for example, BYD is now establishing electric vehicle manufacturing in Brazil, with production of 150,000 vehicles per year by early 2025. In both scenarios this starts a fierce competition with the incumbents, companies such as VW who has already announced it will be adding $1.83 billion to its existing $1.4 billion investment (totalling $3.2 billion) in its Brazilian business and will be launching 16 new hybrid and electric models over the next five years.

This competitive trend in Brazil takes hold and change accelerates. At the same time, big companies active in Brazil are slowly phasing out their global combustion engine businesses and the flex-fuel combustion engine business in Brazil, while maybe having a bit more staying power, eventually suffers the same fate and comes to an end. For a global player, it becomes too expensive to maintain as a standalone business for one country.

As well as the competitive push, there is a pull from the ethanol producers. Initially there is concern as their market starts to shift, but this spurs the deployment of ethanol to jet fuel conversion technology in Brazil and the Brazilian ethanol producers find themselves making a high value product in strong demand around the world. The airlines need SAF and there isn’t enough global production, hence the pull. The bioenergy business in Brazil shifts as a result. The illustrations below show the shift from 2023 to 2050 in Sky 2050. The same shift happens in Archipelagos, but it isn’t as pronounced.

The change in Brazil is so rapid that the country becomes among the earliest to eliminate oil-based fuels from aviation and move entirely to alternatives, mainly bio-based SAF. In both Sky 2050 and Archipelagos oil-based Jet-A1 is phased out completely during the 2060s. This could mean that as well as the country exporting bio-based SAF, airlines in Brazil could transfer some of the lead they will have in SAF uptake through book-and-claim systems to other airlines around the world.

So that is the passenger vehicle story behind the Brazil scenarios. It’s not a prediction or a forecast, but a plausible outcome for the country given the very visible trends and pressures we can see today.

To complete the story, here’s an AI rendition (thanks to Bing and Copilot) of Ipanema beachfront in 2050, with electric cars traversing Av. Vieira Souto.

Note: Shell Scenarios are not predictions or expectations of what will happen, or what will probably happen. They are not expressions of Shell’s strategy, and they are not Shell’s business plan; they are one of the many inputs used by Shell to stretch thinking whilst making decisions. Read more in the Definitions and Cautionary note. Scenarios are informed by data, constructed using models and contain insights from leading experts in the relevant fields. Ultimately, for all readers, scenarios are intended as an aid to making better decisions. They stretch minds, broaden horizons and explore assumptions.

Leave a comment