On February 6th the European Commission published its Communication and Impact Assessment (IA) for a 2040 Climate Target for the EU, recommending a net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions target of 90% against a 1990 baseline. According to the IA, this means less than 850 MtCO2-eq of GHG emissions remaining in 2040.

Scenario analysis provides a useful mechanism for looking at such future goals, so this discussion is in part framed around the EU data in our two Energy Security Scenario stories, Archipelagos and Sky 2050. These are stories that are full of technology and innovation, with rapid change resulting. Firstly, just a reminder of the two scenarios:

Archipelagos depicts a global narrative of shifting political winds driving the transition away from fossil fuels. Despite encountering challenges, the pace of the transition accelerates due to heightened security concerns and competition. This scenario envisions a world where energy security takes precedence over emission management.

Sky 2050 explores a world in which long-term climate security is the primary anchor. Society rapidly moves towards net-zero emissions but doing so requires major interventions from policymakers in the energy system.

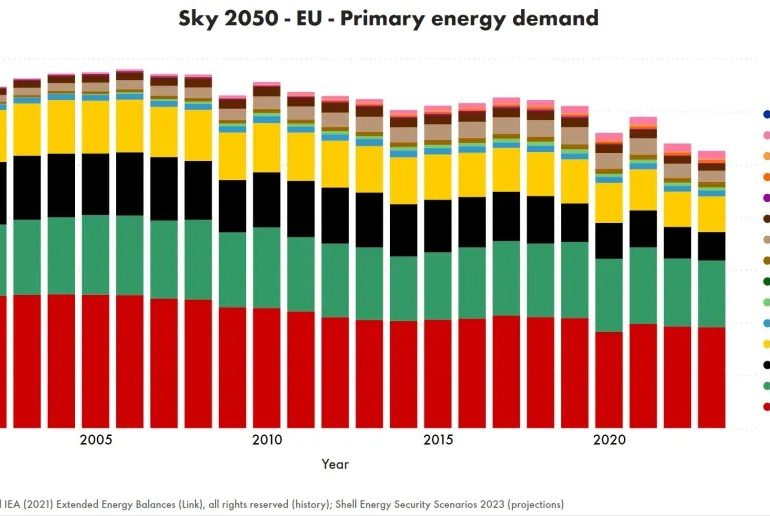

The goal for 2040 means systemic change for the EU energy system in 16 years. This is in stark contrast to the path that has largely been followed over the past 20 years where emissions have been progressively squeezed through efficiency, industrial upgrades, wind and solar at times of abundant wind and sunshine, some use of biomass for power generation and the first wave of electric vehicle uptake in most places in combination with biofuel blending. The energy system has certainly shifted since 2000 but it hasn’t materially changed, except for the use of coal which has more than halved since 2000.

In 2000 fossil fuels made up 78% of the primary energy system and by 2023 this had fallen to 71%. But a 90% fall in emissions by 2040 will mean almost no fossil fuel use by that time, or where there is ongoing fossil fuel use, emissions must be captured and stored or compensated by removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This is because agricultural emissions, but particularly methane from rearing cattle, make up much of the 10% of emissions that would be left. Today in the EU, methane emissions account for around 10% of total GHG emissions and of that methane, three quarters comes from agriculture and waste.

This is why I have framed the discussion in terms of systemic change, meaning that by 2040 the energy system in Europe looks nothing like the energy system of today. Key technologies that must be fully commercialised and scaled up over the next sixteen years include;

Energy storage, such that a very high renewables contribution to electricity can be managed during the night and/or when large areas on the EU are covered by high pressure systems with typically low wind speeds.

Grid development and interconnections, again to manage renewable intermittency but in the shorter term to allow new renewable projects to connect to the grid.

Full acceptance of electric vehicles and no gaps in the recharging network, anywhere. Ideally, only electric vehicles will be purchased by consumers from 2030 onwards for a 2040 90% goal. The average lifetime of a passenger vehicle in the EU is 12 years, but this varies widely from Denmark (8.5 years) to Greece (17 years). As such, some form of early scrappage incentive may be required.

A fully operational solution for trucks, perhaps ranging from electric trucks for shorter haul operation to hydrogen fuel cell for long distance heavy freight vehicles. In some categories of truck today there is no commercial solution, although development activity in the sector is high.

Sustainable aviation fuels making up between a third and half of aviation fuel needs, compared with less than 1% today. In addition, a fully established synthetic fuel capacity must be in place producing some 200,000 barrels per day of synthetic aviation fuel. There is none today. But the Commission document sees some 75-100 million tonnes of carbon dioxide captured each year by 2040 for synthetic fuels. That’s about 25 million tonnes of carbon or 30 million tonnes of hydrocarbon fuel, which is 500,000 barrels per day of production. The large Shell synthesis plant in Qatar (which uses natural gas as its source of hydrogen and carbon) is 150,000 barrels per day and the largest in the world, so the EU needs three of these but with hydrogen from electrolysis and carbon dioxide capture at the back end. Since the Shell facility started up over a decade ago, no new large synthesis plants have been built anywhere. The technology is there, but these are complex processes.

Direct air capture (DAC). This is a nascent technology that has emerged from the USA, Canada and Switzerland. Most of the global activity in DAC is outside the EU, although there are a handful of start-up companies in Europe.

Natural gas for home heating and cooking being rapidly phased out in favour of electricity, or in some instances bio-methane as a direct substitute for natural gas.

Widespread use of electricity, hydrogen or biomethane in industry, but almost no coal. The latter means a radical change for the roughly 50 remaining EU blast furnaces all running on coal.

There is considerable activity in all these areas across the EU and certainly substantial change will happen over the next 15-20 years. But one thing is almost certain, there will be fossil fuels being used in the EU in 2040. Even the EU Commission recognises this and as such, they state there is a need for carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon dioxide removals to reach the 2040 goal. But this need goes way beyond recognition, the requirement is for some 300+ million tonnes per annum of carbon dioxide capture through industrial processes (including direct air capture) and 300 million tonnes of land-based removals, such as through changes in forestry and agricultural practices. For the industrial capture of carbon dioxide, about 200 million tonnes will be stored geologically. That’s 200 significant commercial facilities like the Shell Quest CCS plant in Alberta, Canada. It’s also about the same as the number of facilities in Sky 2050. By contrast in Archipelagos in the EU there are 20 such facilities by 2040.

For the CCS requirement, if this were the USA, I might think of this task as challenging yet achievable. But it’s the EU, not the USA with its established carbon dioxide pipeline network, numerous existing and in development projects and clear business model for CCS through the Inflation Reduction Act tax credits. Readers of this blog will know that I have posted dozens of stories over the years, many about the EU, sharing my frustration at the slow progress of CCS. The sum total of operational (not pilot plants) CCS facilities in the EU is zero, although there are two projects operating in Norway and there is actual construction on several sites within the EU. To be fair, according to a November report from the Global Carbon Capture and Storage Institute, interest in CCS in the EU is surging, with the number of commercial-scale CCS projects in various stages of development in Europe rising 61% since last year and reaching 119 in 2023. For this more upbeat view of EU efforts, see here.

There isn’t a technical reason that would stop 200 facilities from being built, which is why they exist in Sky 2050, but there are political, social and commercial reasons why this may be a step too far for the EU. For example, unlike the USA, clear business models for CCS and removal technologies aren’t in place, there are numerous social and civil community objections to facilities being built and political will on CCS has always been difficult to muster.

For the removals part of the story, there is a significant dependency on change in the agricultural sector, which erupted into protests over other environmental goals very recently. In Sky 2050 we assume that such headwinds part as the mutual interest required to solve the climate issue prevails throughout society. But in the EU there are no clear business models in place to encourage farmers to engage in so-called ‘carbon farming’, meaning practices that result in an increasing carbon stock within the soil. There is some discussion, but in practice such initiatives take years to mature and deliver. Australia has had such a model running for over a decade and only now there is sector discussion around a Carbon Farming Industry Roadmap that envisions a vibrant domestic carbon farming industry by 2030 that contributes significantly to Australia’s economy, community and climate repair.

Much more will be written on the EU ambitions, but in the meantime readers may find it useful to look through the Sky 2050 scenario, or a piece of work prepared in 2020 by the Shell Scenario team that looks specifically at the EU.

Note: Shell Scenarios are not predictions or expectations of what will happen, or what will probably happen. They are not expressions of Shell’s strategy, and they are not Shell’s business plan; they are one of the many inputs used by Shell to stretch thinking whilst making decisions. Read more in the Definitions and Cautionary note. Scenarios are informed by data, constructed using models and contain insights from leading experts in the relevant fields. Ultimately, for all readers, scenarios are intended as an aid to making better decisions. They stretch minds, broaden horizons and explore assumptions.

Leave a comment