Conspiracy theories, especially about vaccines, spread like wildfire during the COVID-19 pandemic, but such anti-science thinking is extending far beyond COVID-19. There are now conspiracies about sunscreen, the causes of cancer, and wifi—among other alleged ills—and they are going global.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Anti-vaccine conspiracies have even begun to influence dog owners. A recent study published in the medical journal Vaccine found that around 4 in 10 dog owners in the U.S. thought vaccinating their dogs against diseases like rabies could cause the dogs to get autism, an entirely unscientific belief.

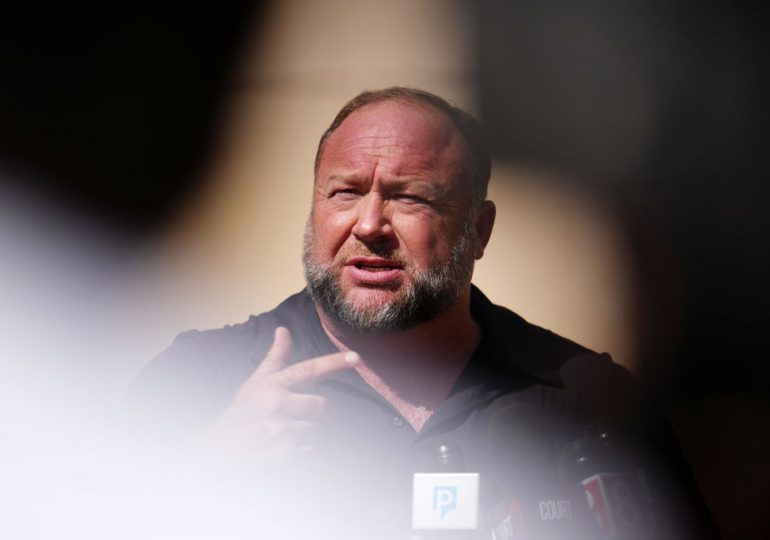

One reason for this expansion in conspiratorial and paranoid beliefs is a new alliance between two groups that might, at first blush, seem to have little in common. Some New Age spirituality and wellness influencers are aligning themselves with extreme right-wing anti-science activists, a merging of interests known as conspirituality. British journalist James Ball calls it “the-wellness-to-fascism pipeline.” The pipeline also runs in the other direction: in the U.S, for example, the far right-wing conspiracy monger Alex Jones sells a variety of wellness products, including diet pills, fluoride-free toothpaste, and tinctures that are claimed to boost male virility.

There are many theories circulating to explain conspirituality, such as the notion that both the wellness and anti-science conspiracy movements attract people who are distrustful of the mainstream, including of mainstream medicine and media. But there’s surely another draw: profit. There are millions—in fact, billions—of dollars to be made from conspiracy capitalism. As the writer Naomi Klein told the New York Times, the two movements are not just joining together through a shared suspicion of power, but also because “their demands fit within the well-worn grooves of individualism, entrepreneurship and self-promotion—the capitalist virtues, that is.”

The spread of conspiracy entrepreneurialism

The curious case of anti-sunscreen “activism” is one illuminating example of conspiracy entrepreneurialism.

In the U.S., Dr. Joseph Mercola, a Florida osteopathic physician, is well known for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, and was identified by the Center for Countering Digital Hate as one of the most prolific peddlers of anti-vaccine falsehoods. At the same time, he is selling alternative wellness products that have gained him an estimated net worth in excess of $100 million.

Mercola has falsely claimed that medically-approved sunscreens are dangerous and recommends you “steer clear” of them because they “interfere with natural vitamin D production.” He urges us to consider UVB as the “good guy.” He is dangerously wrong. Both types of ultraviolet (UV) rays, UVB and UVA, can damage your skin. While it is true that UVB does not penetrate the skin as deeply as UVA, UVB is far from harmless and UVB rays are thought to cause most skin cancers. It comes as no surprise to discover that Mercola is selling his own brand of what he calls “natural” sunscreen. A similar idea is perpetuated by Pete Evans, celebrity chef, author and influencer in Australia, the country with the highest skin cancer rates in the world. He falsely argues that sunscreens contain “poisonous chemicals,” such as oxybenzone and nanoparticles, and rob the body of Vitamin D.

In South Africa, Dr. Naseeba Kathrada pivoted from selling beauty and weight loss products to speaking about how to use potentially harmful “natural” supplements to “detox” after a Covid vaccine. She also runs a fear- and misinformation-filled Telegram group and on community radio stoked fears around childhood vaccination during a measles outbreak. She joined a cohort of doctors and lawyers who combined advocacy for ivermectin, which is ineffective at preventing or treating COVID-19, with anti-vaccine rhetoric.

Zandré Botha, a “multi-dimensional healer,” released a clip that went viral during South Africa’s COVID-19 vaccination campaign, which was featured on the online show hosted by U.S. far-right personality Stew Peters. Botha falsely claimed her “live-blood analysis” showed “nanoparticles” in the blood of vaccine recipients, while selling an unproven “post COVID injection protocol” along with a spiritual testimony through her website. Meanwhile, “indigenous” wellness products like “medicinal herbal teas” are advertised as a “COVID-19 Buster,” and are promoted to people like South African celebrity chef Lesego Semenya days before he died of COVID-19. Kathrada and other anti-vaccine doctors and activists feature prominently on the website of the pseudo-medical World Council for Health, whose “Principles of a Better Way” exude conspirituality.

The durability of misinformation

One problem with this kind of misinformation is that once it gets under the skin, it’s hard to correct. In an intriguing study, American adults were randomly divided into three groups to view simulated Facebook videos. One group watched a video that promoted sunscreen, the other watched a fake interview with a doctor claiming that sunscreen was unhealthy because it damaged your DNA, accelerated aging, and increased the risk of cancer. Those who saw the misinformation video reported being significantly less likely to wear sunscreen when going out in the sun.

In a third group, simulated comments were posted designed to correct the misinformation video in real time—but these real time corrections did not significantly increase people’s intentions to wear sunscreen. Trying to correct misinformation is not only hard, but can sometimes even make more people believe them more deeply.

Read More: The Conspiritualty of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

In the U.S., wellness products and services–which include gym memberships, yoga, and meditation classes–are worth at least $450 billion a year. While some of these services, like gyms, are subject to legislation and regulation, “natural” products have so far escaped scrutiny, so it’s no surprise that the industry is doing all it can to fight legislation that would regulate them. For example, in both Canada and New Zealand, recent legislation to tighten regulation of natural products, in line with medical products, was fiercely opposed by the natural health lobby. The lobby argued that the regulation favored the pharmaceutical industry, framing the regulation as ‘an assault’ on the natural products industry.

The Big Wellness industry is increasingly borrowing its anti-regulation tactics from the playbooks of Big Pharma, Big Food, and Big Tobacco. In the U.S., the offices of the Natural Products Association (NPA) are a stone’s throw from the Capitol, and its President and CEO, Dan Fabricant, admits it is lobbying pretty much every day, with up to a dozen lobbyists working at any one time.

One of the most contested issues of late was last year’s bipartisan Dietary Supplement Listing Act, which would have required all manufacturers of natural products and supplements to register with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) a full list of ingredients, as well as provide relevant warnings, precautions, and allergen statements. Its supporters, including the Council for Responsible Nutrition and the American Medical Association, argued it would have helped the FDA identify and warn consumers about unsafe products, and give doctors easy access to a database to help determine which natural products were appropriate. The bill, opposed by the natural products industry, died in committee.

How to fight back against conspirituality

Conspiratorial anti-science wellness influencers who spread disinformation about evidence-based medicines, vaccines, and sunscreen while hawking their own “natural” products are putting public health at risk. How best can scientists push back?

There’s a range of strategies we must use. One helpful approach is to “inoculate” the public against misinformation—that is, warn them via social media, for example, that unscrupulous influencers will try to peddle anti-scientific notions and arm them with scientific counter-arguments that neutralize the misinformation. A recent review of 42 studies of such inoculation found that it enhanced “individuals’ ability to discern real information from misinformation.” Another strategy is to point out that the merchants of disinformation are motivated by profit. Improving health literacy among the public may help them discern misinformation, particularly in regions where health information contains jargon or words in the dominant languages like English that don’t translate well into widely spoken vernacular. Scientists may also help through a commitment to more research (similar to intervention trials) into the effectiveness of strategies to counter misinformation and the impact on public health.

Anti-science wellness influencers will surely keep pushing ever more wacky and dangerous treatments, like perineum sunning, sun-gazing and correcting your bad eyesight with spiritual healing instead of glasses. Pushing back effectively has become more urgent than ever.

Leave a comment