New Guinea’s diversity of life, cultures and landscapes has long inspired prominent scientists, from Alfred Russel Wallace to Jared Diamond. Sitting just below the equator at the nexus of Asia and Australia-anchored Oceania, the island’s expansive coastline rings a rugged interior that stretches to 4,000-meter-high (13,000-foot) mountains and active volcanoes. The people who live on the island speak more than a thousand languages. And there are 843 species of birds alone that call the island home, according to Avibase, the global bird database.

So it was little surprise to many researchers when a study cataloging New Guinea’s plant species came out Aug. 5 in the journal Nature, confirming that it’s the most botanically diverse island on Earth.

“You go above it in a helicopter, and there’s just a huge gorge, then a massive, vertical mountain and then another huge gorge and then another mountain,” Mason Campbell, a botanist and adjunct research fellow at James Cook University in Cairns, Australia, said in an interview.

The habitats are “ideal for speciation,” added Campbell, who wasn’t involved in the research. “They get isolated quite easily from one another and start diverging.”

The authors came up with a list of 13,634 plant species on the island — nearly 2,000 more than Madagascar, the island with the planet’s second-most diverse vegetation. But along with that floristic splendor, a host of threats face New Guinea. The island’s area is split roughly in half between two Indonesian provinces in the west and the country of Papua New Guinea in the east. On the whole, the diverse human population of the island is among the world’s poorest, with low schooling and literacy rates and a life expectancy of around 64 years. (For most countries in Western Europe, that figure is greater than 80 years.)

Political leaders and corporations often cite such statistics to justify efforts to boost rural economies, arguing that cash-paying jobs, access to health care and education, and connections to markets will lift rural communities out of poverty — tenuous promises at best, say many human rights advocates. But the resulting surge of logging, mining and oil palm and other agricultural plantations, along with plans for a vast road network to link distant communities with markets and cities, has put the diversity documented in this study at risk.

Protecting forests before they’re gone

The island is also something of a natural laboratory, lead author Rodrigo Cámara-Leret said.

“We evolutionary biologists often study fragmented landscapes,” said Cámara-Leret, a postdoctoral researcher at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, in London and Switzerland’s University of Zurich. “[New Guinea] is one of our last arcs of biodiversity, one of the last areas where we really have a chance to conserve what we now know is an extremely diverse place.”

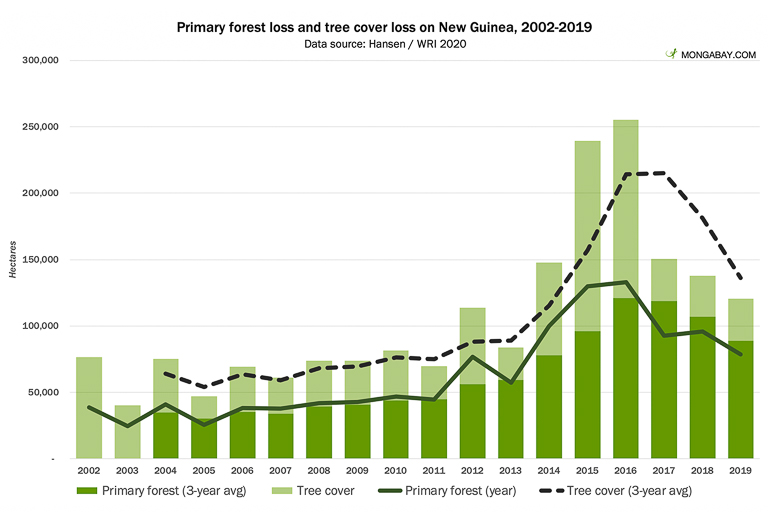

The pace of forest loss on the island has picked up in recent years: More than 11,500 square kilometers (4,440 square miles) of primary forest evaporated between 2002 and 2019 alone, according to data from the University of Maryland and the World Resources Institute. But New Guinea still has some of the most intact primary forest in the tropics, providing a glimpse of ecosystem dynamics that biologists don’t often get, before humans have substantially changed them.

“Most studies now are conducted in hindsight, trying to understand what the effect of anthropogenic disturbance is on the system,” said Cathy Collins, an associate professor of biology at Bard College in New York state, who was not involved in the research. With studies like this one, researchers will then have a fuller understanding of what’s lost if those changes happen.

“It’s amazing to have a species list to be able to later quantify the effect of that disturbance,” Collins said.

That’s not to say humans haven’t had an impact in New Guinea. Cámara-Leret pointed out that people have been there for 50,000 years. But the pace of change to the island’s forests over that time never came close to what’s occurring now, as is true across much of the world’s tropical forests.

New Guinea’s Indigenous peoples have done “a very good job of keeping diversity,” Campbell said.

Despite a long history with the most environmentally disruptive species the planet has ever known, New Guinea remains an unmatched yet fragile crucible of botanical evolution and endemism — 68% of the plants on the island are found nowhere else. How is that possible?

Scientists say that it begins with the island’s complex geology, which, along with subsequent volcanoes, formed a spine of towering peaks that rival Europe’s Alps. The glaciated heights of 4,884-meter (16,024-foot) Puncak Jaya in Indonesia’s Papua province roll down to undulating coastlines and offshore islands, creating habitat for mangroves, lowland jungle and mountain rainforests and grasslands.

Peppering this stew of biodiversity over the millennia has been a smattering of flora from Southeast Asia, Australia and the Pacific Islands of Melanesia that have found their way to the island, Cámara-Leret said.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

On an island that’s the largest in the tropics and second in size only to Greenland worldwide, that’s been a recipe for the vast array of species verified by the scientists.

But the levels of diversity and endemism mean that, in some cases, certain plant species only exist in small geographic areas. Tiberius Jimbo, a co-author of the study and a plant biologist at the Papua New Guinea Forest Research Institute, told Mongabay that he has identified more than 1,000 plant species endemic to Papua New Guinea that qualify for inclusion on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Rarity and limited distributions leave open the possibility that these species could be wiped out with a single bout of logging or creation of an oil palm plantation, as the crop sweeps across the island from western Indonesia and other parts of Southeast Asia.

These land uses can come at the expense of standing forests. But they also often arrive with the construction of new roads. In 2019, Campbell and his colleagues at James Cook analyzed plans in Papua New Guinea to add some 6,300 km (3,900 mi) to the country’s road network by 2022 with the aim of bringing development to far-flung communities. The team predicted that the projected expansion could devastate huge swaths of primary forest.

Plant diversity: The challenge of fragmentation

Just what that means for plant diversity remains something of a mystery, said Collins, who studies the rippling impacts of fragmentation on plant communities.

It’s different with animals, she said. Predicting the impact of fragmentation on a mobile animal like a bear could be as straightforward as determining whether the connections in the landscape are present for it to move between patches of habitat.

“But when we’re looking at plants whose dispersal strategies are so diverse, and many of those organisms like so many trees are long-lived,” Collins said. “It just presents new challenges to understanding the impact of fragmentation on communities.”

Campbell noted that a disturbance like logging can have a seemingly paradoxical effect on the diversity of the forests left behind.

“They can actually get more diverse just after being logged, because it gets invaded by exotic species,” he said. “On top of that, you have all these refugee species coming to try and jump in that last little fragment of forest.”

Such changes can bump up the species count within a specific area in the short term. But the reality is that some of the plants have survived but won’t be able to reproduce, known as “recruitment” among botanists, leaving behind “living dead species,” Campbell said.

“That’s where a fragment is leftover after a road, or something has gone through, and we’ll have a heap of species — say, lonely rain forest trees that live 400-500 years,” he said. “But actually, they’re not going to recruit. The conditions are not what would allow the seedlings to grow.”

“I think one of the greatest threats at the moment is road building,” Cámara-Leret said, “because there are plans to really increase roads everywhere.”

“Even a report by the World Bank was very critical of existing plans to increase both roads in Indonesian New Guinea,” he added.

But the problems associated with poverty across the island have created a conundrum for policymakers and scientists alike.

Harmonizing development and conservation

“Papua New Guinea is still developing,” said Peter Homot, a co-author of the study and herbarium curator at the Papua New Guinea Forest Research Institute. “We are still going through this process of building the economy.”

Homot and his institute colleague, Tiberius Jimbo, agree that their research could be used to guide government development policy or conservation efforts by NGOs.

“What we knew up to this paper is that there are some important threats to biodiversity, but we were not so knowledgeable about exactly what biodiversity we were talking about,” Cámara-Leret said. “Our checklist in some ways is the first step to have this baseline.”

Having that baseline of species is a critical step, Campbell said. “You can’t really include them in conservation initiatives,” he added, “if you don’t know what’s there.”

But getting the research into the hands of policymakers isn’t always easy.

“I don’t see that happening in the near future,” Campbell said, “but that would be the best way to get practical outcomes.”

Still, the team believes that the research could help influence policy. One of the authors, Charlie Heatubun, is a botany professor at Universitas Papua in Manokwari, the capital of Indonesia’s West Papua province, as well as the director of the provincial government’s research and development agency.

Since 2015, West Papua has called itself a “conservation province.” Then, in 2018, the governors of West Papua and Papua, signed the Manokwari Declaration, committing to protecting 70% of the land on the Indonesian half of the island.

What’s more, for several years, Heatubun has been working with Kew Gardens to identify “tropical important plant areas,” or TIPAS, in the province. The goal is to identify threatened habitats before they’re wiped out, and he said that this research detailing New Guinea’s plant diversity bolsters the effort and reflects a shift in how decisions are made in the province.

In West Papua, he said, “We have a policy that we need to increase our livelihood and economic [development] for the people.”

But leaders also have the science demonstrating the biodiversity present in the area, helping them identify areas that need protection.

“We can have more confidence that the policy we take now is sustainable development,” Heatubun said. “Previously, many policies were made without any scientific basis. But now we have started to make policies based on scientific data.”

Leave a comment