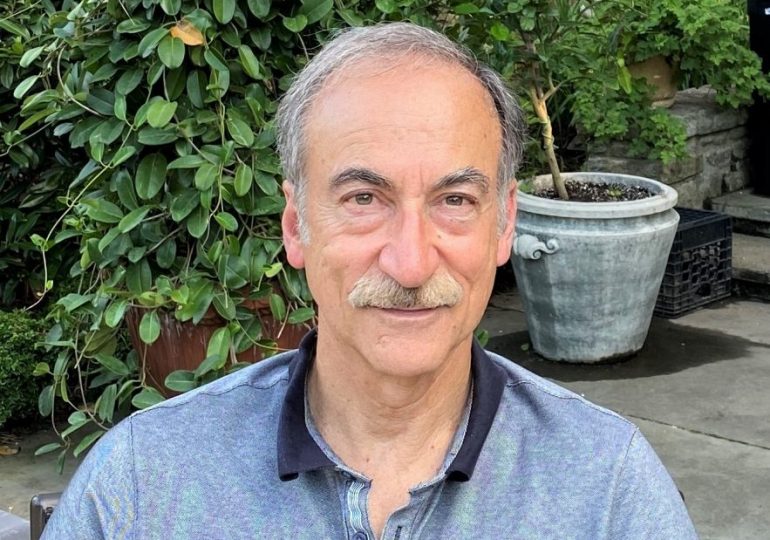

By STEVEN ZECOLA

This study tracks the decades-long journey to harness alpha-synuclein as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Steven Zecola an activist who tracks Parkinson’s research and was on THCB last month discussing it, offers three key changes needed to overcome the underlying challenges.

A Quick Start for Alpha-Synuclein R&D

In the mid-1990’s, Parkinson’s patient advocacy groups had become impatient by the absence of any major therapeutic advances in the 25 years since L-dopa had been approved for Parkinson’s disease (PD).

The Director of National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) set up a workshop in August 1995 that featured scientists with expertise in human genetics who might open novel avenues for PD research.

One such scientist, Robert Nussbaum, made the following remarks at the workshop:

“…finding genes responsible for familial Parkinson’s should be helpful for understanding all forms of the disease. Techniques now available should allow researchers to find the genes responsible for familial Parkinson’s disease in a relatively short time.”

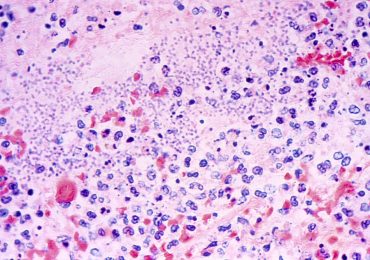

Two years later in 1997, Spillantini et al. showed that alpha-synuclein (A-syn) was a major contributor of abnormal clusters of proteins in the brain, not only in patients with synuclein mutations but, more importantly, in patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease as well.

As Nussbaum had predicted, progress had occurred rapidly. President Clinton in his 1998 State of the Union address, said:

“Think about this, the entire store of human knowledge now doubles every 5 years. In the 1980’s, scientists identified the gene causing cystic fibrosis. It took 9 years. Last year scientists located the gene that causes Parkinson’s disease in only 9 days.”

The NIH is Asked to Take a Leadership Role

Shortly after President Clinton’s call to action, a Senate Committee asked the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to develop a coordinated effort to take advantage of promising opportunities in PD research.

In response, the NIH and the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (NINDS) held a major planning meeting that included all components of the PD community. The group’s recommendations formed the basis of a five-year PD Research Agenda.

The Research Agenda was codified in a comprehensive 42-page report that covered all aspects of research from better understanding the disease, to creating new research capabilities, to developing new treatments, and to enhancing the research process.

Noting the “remarkable paradigm shift in Parkinson’s disease research” from the discovery of the effects of alpha-synuclein, the report stated that:

“New insights into the role of synucleins in the pathobiology of Parkinson’s disease would accelerate discovery of more effective therapies and provide fresh research opportunities to advance our understanding of Parkinson’s disease”.

NIH invested nearly $1 billion from FY 2000 to FY 2004 to implement the PD Research Agenda. A-syn research would be funded out of the funds allocated to the categories of Genetics and Epidemiology, with both categories targeted to receive about 15% of the overall spending.

Overall, there were 19 broad categories with spending authorizations, including $32.7 million allocated to Program Management and Direction.

When the PD Research Agenda reached the end of its 5-year span, NINDS sponsored a second PD Summit which was held in June 2005. It brought together an industry-wide consortium to assess the progress over the previous five years and to develop future directions for PD research.

The participants generated more than fifty specific recommendations. NIH considered these plans and the unmet goals from previous efforts and developed a 3-year Plan.

A major focus of that Plan was to identify and intervene with the causes of PD.

As reiterated in the 2006 Plan:

“…Understanding the role of alpha-synuclein may enable strategies to selectively block the harmful effects associated with this protein as a novel approach to treatment of PD”.

NINDS noted that:

“While PD is not a rare or orphan disease, other more prevalent diseases such as stroke, obesity and diabetes offer considerably larger “markets” for drug therapies than does PD. Thus, pharmaceutical companies have primarily focused on medicinal chemistry and alterations of existing PD or other neurological drugs (e.g., dopamine agonists) rather than investing in new drugs.”

In essence, NINDS recognized the financial conundrum of drug development for A-syn and other PD therapies, but looked to academia to solve the problem through its grant program.

Lacking success from the efforts of the 2006 Plan, NINDS organized another conference in January 2014 called: Parkinson’s Disease 2014: Advancing Research, Improving Lives. The purpose of this initiative was to identify significant challenges and to highlight the highest priorities for advancing research.

Thirty-one recommendations were provided. The summary of the conference included the Top 3 priorities for clinical research, translational research, and basic research. Under basic research, priorities 1 and 2 related to alpha-synuclein.

Given that the work specified for A-syn research was still at an early stage of basic research in 2014, it is clear that a large gap existed between the previous NINDS priorities for A-syn and what was delivered.

Private Interests Finally Move Forward with Alpha-Synuclein

Recognizing the continuing lack of progress and the need for funding, the Michael J. Fox Foundation announced a $10-million “Ken Griffin Alpha-synuclein Imaging Competition” in 2019 to spur development of a critical and elusive imaging research tool for Parkinson’s disease.

In March 2023, MJFF announced that the three initial Alpha-synuclein imaging competition teams — AC Immune, Mass General Brigham and Merck— made tremendous advancements in the development of different alpha-synuclein tracer methods.

MJFF awarded Merck an additional $1.5 million to continue the work and bring its tool to life. The first-in-human clinical trial of its alpha-synuclein PET tracer began in 2023.

Additionally, after more than two decades of basic research, five private research companies filed applications with the FDA and have initiated early-stage PD trials.

Neuropore Therapies and UCB are collaborating on an oral small molecule, which aims to prevent the formation of alpha-synuclein clusters.

Prothena Biosciences, in conjunction with Roche, is testing a humanized anti-alpha-synuclein antibody.

Biogen is investigating another monoclonal antibody against alpha-synuclein.

AFFiRiS, an Austrian biotech company, is testing an alpha-synuclein vaccine. AC Immune has recently announced the acquisition of all of AFFiRiS’ assets and underlying intellectual property related to its vaccine candidates targeting a-syn.

Vaxxinity uses an immunotherapy candidate codenamed UB–312 to target toxic forms of aggregated α-synuclein in the brain to fight Parkinson’s. Its Chairman recently said that: “Our findings suggest UB-312 could transform Parkinson’s care, offering hope for improved outcomes with a disease-modifying treatment”.

As with all R&D projects, there are many remaining challenges in the development of A-syn therapies before reaching the market. Nevertheless, assuming that at least one of the five on-going trials will be successful, we can expect a therapy utilizing A-syn will be approved by the FDA within the next 5-8 years. The net effect is that the overall development window between A-syn’s discovery in 1997 and its application to patients would be approximately 35 years – assuming that the research goes relatively smoothly from here.

Given its performance to date, the view from NIH regarding PD research is:

“… Our failures in bringing treatments to the goal line are due to remaining large gaps in knowledge of the underlying biology that causes and drives the disease. As we fill in these gaps, the chances of success will increase. Some of the gaps we know about, others we only find out about when the science opens another door”.

Why Has This Research Taken So Long?

With the benefit of hindsight, we can point to two areas that accounted for the greatest obstacles to progress – focus and resources.

In reading the PD research plans and reports from 2000, 2006 and 2014, it appears that NINDS threw everything it knew about PD into the hopper. There were hundreds of recommendations, projects and so-called priorities. But a key factor of success in research is having a team of motivated scientists with the necessary skills, knowledge and thinking ability to solve a finely-honed question.

There simply are not enough great minds to track down all of the “to do’s” in the three NINDS PD research plans. Also, communications and networking are important components of scientific advancement, yet the capability to network with the widespread participation in the small grants program was lacking.

The implication of using the term “focus” is that it comes with the assignment of responsibility and accountability if the priority doesn’t get done. There appears to be little outside oversight of the efficiency and effectiveness of the research dollars that were utilized on A-syn or other PD research projects. If anything, NIH seems content with the output.

Finally, NIH/NINDS knew there was a funding problem in crossing the Valley of Death from basic research to clinical trials, but these organizations fell back to their comfort zone, namely small grants to academicians. This strategy did not produce the necessary results.

A Better Approach

In 1998 and thereafter, alpha-synuclein needed a swat team of top-flight researchers along with a commitment for additional funds as the project progressed out of basic research and through the requisite clinical trials.

To address the shortcomings to date, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should step in and 1) narrow the PD research priority list to the top candidates, 2) require the establishment of a robust communications network for sharing information and 3) relax the FDA regulations for PD to help level the fund-raising playing field.

In particular, HHS/NIH/NINDS must recognize that investments in new healthcare therapies such as A-syn come with very high risks and those risky investment dollars get to choose between healthcare therapies that go through 15+ years of basic research and expensive clinical trials and other opportunities that can be launched in less than a year.

Of paramount concern, the FDA’s regulatory scheme has had two deleterious effects on fund-raising. First, the FDA overhang has dried up interest in angel and venture capital investing in potential therapies such as A-syn. The result has been a Valley of Death between basic research and drug development. Second, even if the initial Valley can be crossed through government grants or non-profit donations, the FDA regulatory scheme puts an enormous burden on companies to raise scores of millions of dollars for lengthy clinical trials that face an uncertain regulatory outcome.

NIH/NINDS have not recognized that even without any direct role in fundraising, the FDA dominates the fund-raising process. For example, approximately 90% of fundraising for R&D is based on claims tied to regulatory milestones. Investors are well-aware of the challenges of the FDA approval process and it curbs investor interest.

Even in basic research, the FDA has had a large influence on scientific progress. For the academic entrepreneur, early development of an effective regulatory plan can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, regulatory strategy becomes a critical component of the innovation process.

HHS must also recognize that the FDA has safety-first culture and a not-invented-here syndrome when it comes to any proposed changes to its processes.

The solution to these challenges, in part, entails HHS imposing a relaxed regulatory scheme for PD. For example, the FDA should be excludedfrom Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials and from providing any guidance to researchers prior to Phase 3 clinical trials. Such a change will speed development, unleash innovation, and improve early-stage fund-raising.

Second, to improve performance of the research endeavors, NINDS should be tasked to develop and manage a formal, hub-and-spoke, communications network among all stakeholders involved in PD research. ClinicalTrials.gov does not satisfy this requirement because it contains misleading information.

Facilitating regular exchanges of information, data sharing, and collaboration should help to maximize the impact of research efforts and avoid duplication of work. For the investment community, a partition in the hub with investment-related information would help to build a bridge over the Valley of Death and bring more funding to potential therapies such alpha-synuclein.

This investor-related partition of the communications office should generally be housed by MBAs (rather than by Ph.D.’s) who are focused on communicating high value research endeavors with the not-so-subtle intent of fomenting an interest in investments. NIH should consider hiring an investment banking firm to assist in setting up the investor-related component of this information network.

The third recommendation for change is that NIH should convene a very small group of experts working on PD research to identify the three most-likely-to-succeed paths to a cure. It should ensure that those paths have adequate personnel and sufficient research dollars for completion. Progress should be monitored on a regular basis.

Lastly, I should mention that the Michael J. Fox Foundation has done an excellent job on a number of important issues and should be a major part of any restructure going forward. For example, HHS could outsource the communications hub to MJFF.

The bottom line is that all components of the PD industry, including the FDA, must be on the same page in terms of finding a cure for PD within a reasonable amount of time given existing resources whether it be with alpha synuclein or other therapies. Such has not been the case with A-syn to date, and similarly, we have witnessed that the entire research effort for PD has underperformed – and will continue to underperform – in the absence of corrective action.

The Long and Tortured History of Alpha-Synuclein and Parkinson’s Disease

Preface

This study tracks the decades-long journey to harness alpha-synuclein as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease. The author offers three key changes needed to overcome the underlying challenges.

A Quick Start for Alpha-Synuclein R&D

In the mid-1990’s, Parkinson’s patient advocacy groups had become impatient by the absence of any major therapeutic advances in the 25 years since L-dopa had been approved for Parkinson’s disease (PD).

The Director of National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) set up a workshop in August 1995 that featured scientists with expertise in human genetics who might open novel avenues for PD research.

One such scientist, Robert Nussbaum, made the following remarks at the workshop:

“…finding genes responsible for familial Parkinson’s should be helpful for understanding all forms of the disease. Techniques now available should allow researchers to find the genes responsible for familial Parkinson’s disease in a relatively short time.”

Two years later in 1997, Spillantini et al. showed that alpha-synuclein (A-syn) was a major contributor of abnormal clusters of proteins in the brain, not only in patients with synuclein mutations but, more importantly, in patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease as well.

As Nussbaum had predicted, progress had occurred rapidly. President Clinton in his 1998 State of the Union address, said:

“Think about this, the entire store of human knowledge now doubles every 5 years. In the 1980’s, scientists identified the gene causing cystic fibrosis. It took 9 years. Last year scientists located the gene that causes Parkinson’s disease in only 9 days.”

The NIH is Asked to Take a Leadership Role

Shortly after President Clinton’s call to action, a Senate Committee asked the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to develop a coordinated effort to take advantage of promising opportunities in PD research.

In response, the NIH and the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (NINDS) held a major planning meeting that included all components of the PD community. The group’s recommendations formed the basis of a five-year PD Research Agenda.

The Research Agenda was codified in a comprehensive 42-page report that covered all aspects of research from better understanding the disease, to creating new research capabilities, to developing new treatments, and to enhancing the research process.

Noting the “remarkable paradigm shift in Parkinson’s disease research” from the discovery of the effects of alpha-synuclein, the report stated that:

“New insights into the role of synucleins in the pathobiology of Parkinson’s disease would accelerate discovery of more effective therapies and provide fresh research opportunities to advance our understanding of Parkinson’s disease”.

NIH invested nearly $1 billion from FY 2000 to FY 2004 to implement the PD Research Agenda. A-syn research would be funded out of the funds allocated to the categories of Genetics and Epidemiology, with both categories targeted to receive about 15% of the overall spending.

Overall, there were 19 broad categories with spending authorizations, including $32.7 million allocated to Program Management and Direction.

When the PD Research Agenda reached the end of its 5-year span, NINDS sponsored a second PD Summit which was held in June 2005. It brought together an industry-wide consortium to assess the progress over the previous five years and to develop future directions for PD research.

The participants generated more than fifty specific recommendations. NIH considered these plans and the unmet goals from previous efforts and developed a 3-year Plan.

A major focus of that Plan was to identify and intervene with the causes of PD. As reiterated in the 2006 Plan:

“…Understanding the role of alpha-synuclein may enable strategies to selectively block the harmful effects associated with this protein as a novel approach to treatment of PD”.

NINDS noted that:

“While PD is not a rare or orphan disease, other more prevalent diseases such as stroke, obesity and diabetes offer considerably larger “markets” for drug therapies than does PD. Thus, pharmaceutical companies have primarily focused on medicinal chemistry and alterations of existing PD or other neurological drugs (e.g., dopamine agonists) rather than investing in new drugs.”

In essence, NINDS recognized the financial conundrum of drug development for A-syn and other PD therapies, but looked to academia to solve the problem through its grant program.

Lacking success from the efforts of the 2006 Plan, NINDS organized another conference in January 2014 called: Parkinson’s Disease 2014: Advancing Research, Improving Lives. The purpose of this initiative was to identify significant challenges and to highlight the highest priorities for advancing research.

Thirty-one recommendations were provided. The summary of the conference included the Top 3 priorities for clinical research, translational research, and basic research. Under basic research, priorities 1 and 2 related to alpha-synuclein.

Given that the work specified for A-syn research was still at an early stage of basic research in 2014, it is clear that a large gap existed between the previous NINDS priorities for A-syn and what was delivered.

Private Interests Finally Move Forward with Alpha-Synuclein

Recognizing the continuing lack of progress and the need for funding, the Michael J. Fox Foundation announced a $10-million “Ken Griffin Alpha-synuclein Imaging Competition” in 2019 to spur development of a critical and elusive imaging research tool for Parkinson’s disease.

In March 2023, MJFF announced that the three initial Alpha-synuclein imaging competition teams — AC Immune, Mass General Brigham and Merck— made tremendous advancements in the development of different alpha-synuclein tracer methods.

MJFF awarded Merck an additional $1.5 million to continue the work and bring its tool to life. The first-in-human clinical trial of its alpha-synuclein PET tracer began in 2023.

Additionally, after more than two decades of basic research, five private research companies filed applications with the FDA and have initiated early-stage PD trials.

Neuropore Therapies and UCB are collaborating on an oral small molecule, which aims to prevent the formation of alpha-synuclein clusters.

Prothena Biosciences, in conjunction with Roche, is testing a humanized anti-alpha-synuclein antibody.

Biogen is investigating another monoclonal antibody against alpha-synuclein.

AFFiRiS, an Austrian biotech company, is testing an alpha-synuclein vaccine. AC Immune has recently announced the acquisition of all of AFFiRiS’ assets and underlying intellectual property related to its vaccine candidates targeting a-syn.

Vaxxinity uses an immunotherapy candidate codenamed UB–312 to target toxic forms of aggregated α-synuclein in the brain to fight Parkinson’s. Its Chairman recently said that: “Our findings suggest UB-312 could transform Parkinson’s care, offering hope for improved outcomes with a disease-modifying treatment”.

As with all R&D projects, there are many remaining challenges in the development of A-syn therapies before reaching the market. Nevertheless, assuming that at least one of the five on-going trials will be successful, we can expect a therapy utilizing A-syn will be approved by the FDA within the next 5-8 years. The net effect is that the overall development window between A-syn’s discovery in 1997 and its application to patients would be approximately 35 years – assuming that the research goes relatively smoothly from here.

Given its performance to date, the view from NIH regarding PD research is:

“… Our failures in bringing treatments to the goal line are due to remaining large gaps in knowledge of the underlying biology that causes and drives the disease. As we fill in these gaps, the chances of success will increase. Some of the gaps we know about, others we only find out about when the science opens another door”.

Why Has This Research Taken So Long?

With the benefit of hindsight, we can point to two areas that accounted for the greatest obstacles to progress – focus and resources.

In reading the PD research plans and reports from 2000, 2006 and 2014, it appears that NINDS threw everything it knew about PD into the hopper. There were hundreds of recommendations, projects and so-called priorities. But a key factor of success in research is having a team of motivated scientists with the necessary skills, knowledge and thinking ability to solve a finely-honed question.

There simply are not enough great minds to track down all of the “to do’s” in the three NINDS PD research plans. Also, communications and networking are important components of scientific advancement, yet the capability to network with the widespread participation in the small grants program was lacking.

The implication of using the term “focus” is that it comes with the assignment of responsibility and accountability if the priority doesn’t get done. There appears to be little outside oversight of the efficiency and effectiveness of the research dollars that were utilized on A-syn or other PD research projects. If anything, NIH seems content with the output.

Finally, NIH/NINDS knew there was a funding problem in crossing the Valley of Death from basic research to clinical trials, but these organizations fell back to their comfort zone, namely small grants to academicians. This strategy did not produce the necessary results.

A Better Approach

In 1998 and thereafter, alpha-synuclein needed a swat team of top-flight researchers along with a commitment for additional funds as the project progressed out of basic research and through the requisite clinical trials.

To address the shortcomings to date, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should step in and 1) narrow the PD research priority list to the top candidates, 2) require the establishment of a robust communications network for sharing information and 3) relax the FDA regulations for PD to help level the fund-raising playing field.

In particular, HHS/NIH/NINDS must recognize that investments in new healthcare therapies such as A-syn come with very high risks and those risky investment dollars get to choose between healthcare therapies that go through 15+ years of basic research and expensive clinical trials and other opportunities that can be launched in less than a year.

Of paramount concern, the FDA’s regulatory scheme has had two deleterious effects on fund-raising. First, the FDA overhang has dried up interest in angel and venture capital investing in potential therapies such as A-syn. The result has been a Valley of Death between basic research and drug development. Second, even if the initial Valley can be crossed through government grants or non-profit donations, the FDA regulatory scheme puts an enormous burden on companies to raise scores of millions of dollars for lengthy clinical trials that face an uncertain regulatory outcome.

NIH/NINDS have not recognized that even without any direct role in fundraising, the FDA dominates the fund-raising process. For example, approximately 90% of fundraising for R&D is based on claims tied to regulatory milestones. Investors are well-aware of the challenges of the FDA approval process and it curbs investor interest.

Even in basic research, the FDA has had a large influence on scientific progress. For the academic entrepreneur, early development of an effective regulatory plan can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, regulatory strategy becomes a critical component of the innovation process.

HHS must also recognize that the FDA has safety-first culture and a not-invented-here syndrome when it comes to any proposed changes to its processes.

The solution to these challenges, in part, entails HHS imposing a relaxed regulatory scheme for PD. For example, the FDA should be excludedfrom Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials and from providing any guidance to researchers prior to Phase 3 clinical trials. Such a change will speed development, unleash innovation, and improve early-stage fund-raising.

Second, to improve performance of the research endeavors, NINDS should be tasked to develop and manage a formal, hub-and-spoke, communications network among all stakeholders involved in PD research. ClinicalTrials.gov does not satisfy this requirement because it contains misleading information.

Facilitating regular exchanges of information, data sharing, and collaboration should help to maximize the impact of research efforts and avoid duplication of work. For the investment community, a partition in the hub with investment-related information would help to build a bridge over the Valley of Death and bring more funding to potential therapies such alpha-synuclein.

This investor-related partition of the communications office should generally be housed by MBAs (rather than by Ph.D.’s) who are focused on communicating high value research endeavors with the not-so-subtle intent of fomenting an interest in investments. NIH should consider hiring an investment banking firm to assist in setting up the investor-related component of this information network.

The third recommendation for change is that NIH should convene a very small group of experts working on PD research to identify the three most-likely-to-succeed paths to a cure. It should ensure that those paths have adequate personnel and sufficient research dollars for completion. Progress should be monitored on a regular basis.

Lastly, I should mention that the Michael J. Fox Foundation has done an excellent job on a number of important issues and should be a major part of any restructure going forward. For example, HHS could outsource the communications hub to MJFF.

The bottom line is that all components of the PD industry, including the FDA, must be on the same page in terms of finding a cure for PD within a reasonable amount of time given existing resources whether it be with alpha synuclein or other therapies. Such has not been the case with A-syn to date, and similarly, we have witnessed that the entire research effort for PD has underperformed – and will continue to underperform – in the absence of corrective action.

Leave a comment