Recently, I wanted a new pair of leather sandals. I narrowed my search down to a few favorite pairs, then compared prices before scouring the reviews. An hour later, I was still pondering which pair was the cutest, how much money I should spend, and whether the company’s return policy was good enough, should I change my mind. My brain was reeling. What used to be a pleasant experience at a physical store—shoe-buying—was now majorly stressing me out, alone in front of my screen.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Going shopping used to be known as “retail therapy.” Indeed, research has shown that traditional brick-and-mortar shopping can ease sadness, at least temporarily, and give people a sense of control.

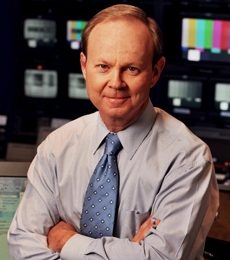

Online shopping, however, is often overwhelming for your brain. Both shopping and the internet can be addictive, and combining them creates a dopamine rush, says Dr. Elias Aboujaoude, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Stanford Medicine—who studies compulsive buying disorder, or shopping addiction—and director of the Stanford OCD Clinic. “Online, the urge to shop can be satisfied much more quickly, making it more difficult to resist.” Anxiety and depression seem to intensify those effects. “One thing that can certainly make it riskier is something like untreated depression, because people are looking for a quick, temporary boost to their mood.”

I was looking for such a mood boost during the early months of the pandemic. Though I didn’t have a shopping addiction, I occasionally coped with my anxiety, stress, and isolation by shopping online. But once my packages arrived, I didn’t want them anymore. What little pleasure I had wrought from shopping online had come from the anticipation of the purchases—not the items themselves.

“The act of filling the cart or purchasing the item can almost feel more powerful than actually getting it,” says Thea Gallagher, a clinical psychologist and associate professor at NYU Langone Health. Past studies have conditioned rats to expect cocaine when a bell rings—but researchers found that they got an intense dopamine rush from the sound of the bell, even when the drug didn’t come. “Obviously, there’s no cocaine in online shopping,” she says, “but there’s a dopamine bump that keeps people coming back for more.”

Online shopping is inevitable—there are, of course, certain things we need. But there are ways to become a happier online shopper.

Focus on “good enough”

There are two types of decision-makers, psychologists say: maximizers and satisficers. Maximizers fret over each decision, intent on getting the “best” no matter how much planning or research it takes. Satisficers, meanwhile, are content with making a choice that ticks the relevant boxes—and then they move on with their lives.

If you need to purchase something, Gallagher says, be the second type of decision-maker, and don’t worry about finding the perfect item. “Research actually shows people who make decisions that are ‘good enough’ are happier and less overwhelmed,” Gallagher says.

Unsave your credit card information

One of the keys to avoiding impulse buys is removing the automatic component of the behavior, says Aboujaoude. A good first step, he says, is not having your credit card and personal information saved on your web browser.

Put a waiting period on all purchases

Whether it’s a day, a week, or a month, consider enforcing a waiting period on all of your non-essential purchases. (I typically paste a link to the item in my phone’s Notes app, then revisit it a week later.)

“My quickest rule is just to sleep on it,” says J.B. MacKinnon, author of The Day the World Stops Shopping: How Ending Consumerism Saves the World and Ourselves. You likely won’t want the item after the waiting period. But if you do, then it probably makes sense to buy it—and at least you’ve developed some self-awareness about your shopping habits, he says. “We often have these urges to consume, but if we took a minute, we’d realize it wasn’t going to bring much to our lives, if anything at all.”

Give yourself a no-buy month

Courtney Carver, author of several books about the virtues of minimalism, says that she became enamored with a simpler life when she decided not to buy anything she didn’t absolutely need for three months.

“Consider a week-long, month-long, or three-month-long shopping ban [where you] don’t shop for anything that’s not essential, if only to give your brain a break from having to seek that next new thing and to assess whether or not that serves you,” says Carver.

When I went on a three-month buying strike, I had more time to focus on pursuits that brought me pleasure (like reading and cross-stitching), and I felt more excited about the purchases I did make. MacKinnon says we develop a stronger attachment to our possessions once we decide to shop less. Small impulse purchases bring a dopamine rush that’s often fleeting and guilt-ridden. Once you start shopping online less and focusing more on meaningful purchases, you’ll likely derive more joy from your items.

“I don’t buy a ton of things, but when I do, I’ve thought about them,” says MacKinnon. “And when I bring them home, I’m happy to have them. They tend to give me enduring happiness rather than flash-in-the-pan happiness.”

Edit your inbox and social media feeds

Experts in the field initially thought online shopping would be better than traditional shopping because people wouldn’t be tempted by in-store marketing and could instead buy only the item they wanted, Aboujaoude says. “Of course, it turned out to be the exact opposite,” he says. “The incredibly sophisticated micro-targeted marketing and advertising that takes place makes some people even weaker in terms of resisting these impulses.”

Unsubscribing from the advertising emails designed to make us shop is one good defense. Unfollowing or muting Instagram influencers is another. They often share posts—sponsored or not—that make us think we need something we never considered buying before. “I think social media has really blurred the line between authentic relationships and transactional relationships,” MacKinnon says.

Don’t fall victim to your aspirational self

I love colorful floral sundresses. But I’m a part-time freelance writer and part-time stay-at-home mom who’s usually wearing leggings and loose thermal tops. It might be nice to picture myself wearing a sundress as I write from a coffee shop or care for my kids—but in reality, I know I’m not going to. Once I began shopping for my actual self instead of my aspirational self, I saw a positive shift in my online shopping habits.

Carver can relate. She recently traveled to Amsterdam during a cold snap, and saw a coat that would’ve been perfect for the freezing weather. But it wasn’t something she’d likely wear once her trip had ended. “I tried to picture future Courtney: Would she wear this coat in her day-to-day life, or is this just a vacation Courtney coat? I decided to wait,” she says, “and just continue layering.”

Leave a comment